September 19, 2022

Inflation Goes Global

Author - Ben McGregor

Gold down as continued high inflation locks in big Fed hike

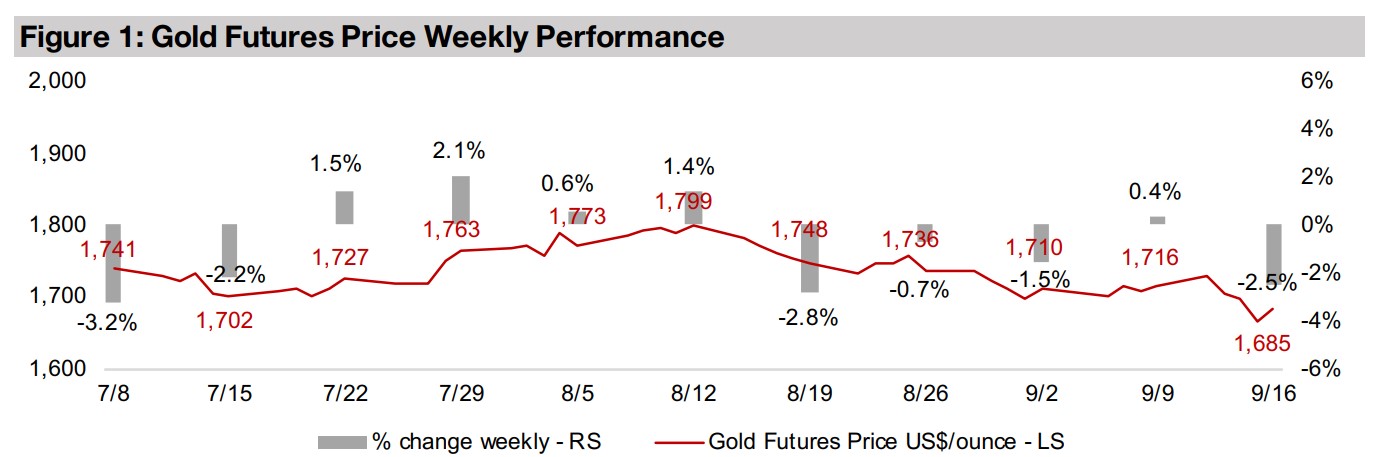

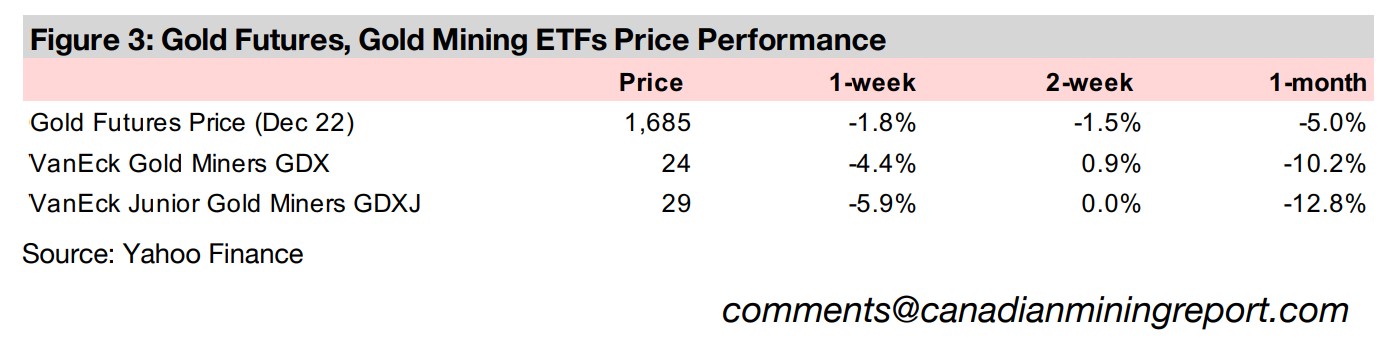

Gold dropped -1.8% this week to US$1,685/oz as inflation in the US remained well above expectations in August 2022 and made it almost a certainty that the US Fed makes a major rate hike, as high as 75 bps, at its upcoming meeting this week.

Considering the effects on gold of global inflation and rate hikes

This week we look at how high inflation is becoming an increasingly global phenomenon, prompting surging interest rates from most of the major global economies and what effects this could have on gold both in the short and long-term.

Inflation Goes Global

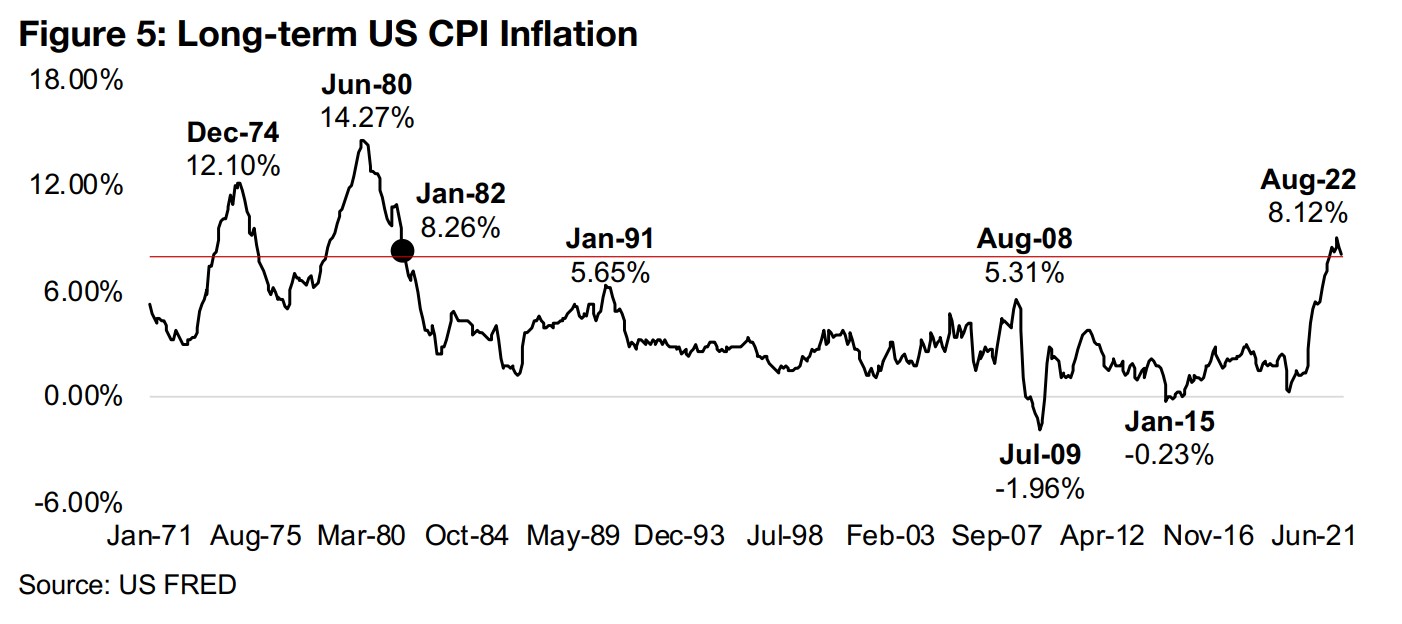

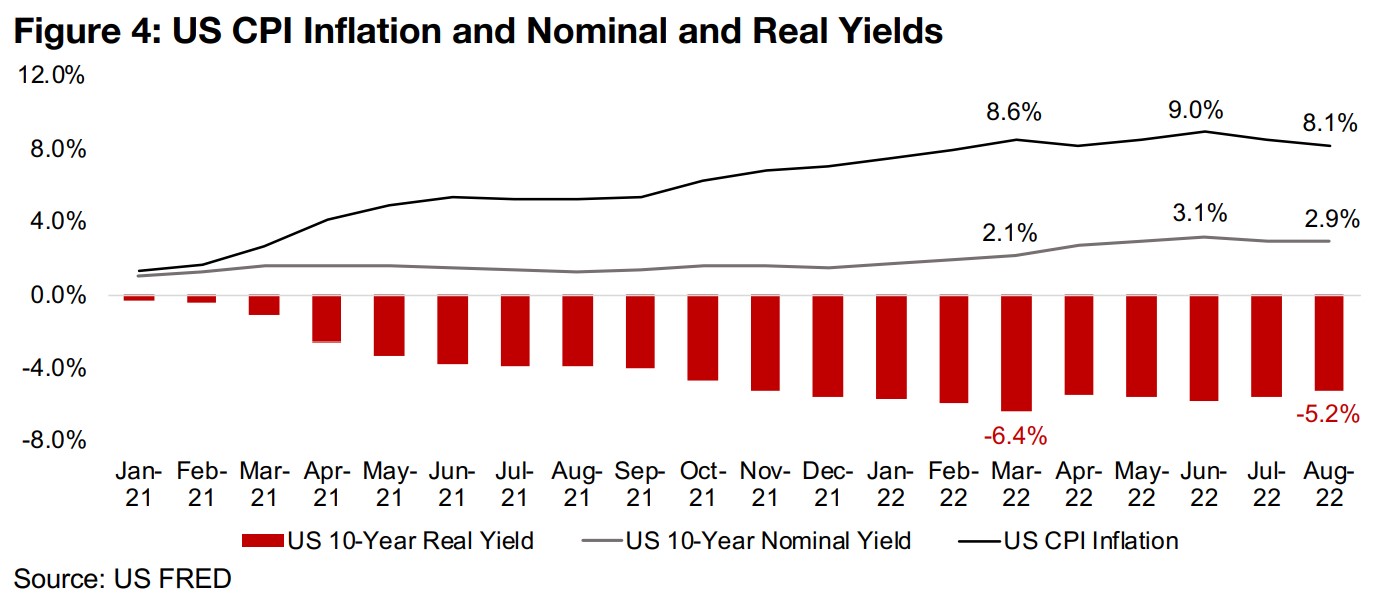

Gold was down -1.8% to US$1,685/oz as expectations that US CPI inflation for August 2022 would decline significantly were dashed when it came in at 8.1% yoy (Figure 4), above consensus and at forty-year highs. This made it near certain that the Fed would make a major hike at its upcoming meeting this week, by up to 75 bps, and drove down gold and the equity markets. For gold, while inflation was still above expectations, it has trended down for the three months, while US 10-year yields have risen. This has made US 10-year real yields less negative, up from lows of -6.4% in March 2022 to -5.2% in August 2022, and while still hardly a great deal, more attractive than six months ago (Figure 5). At the margin this could pull in more investors to US bonds, diverting funds away from gold. On top of this was the rise in the US$ this week, extending over a one-year surge, putting further pressure on gold.

Considering the effects on gold as inflation goes global

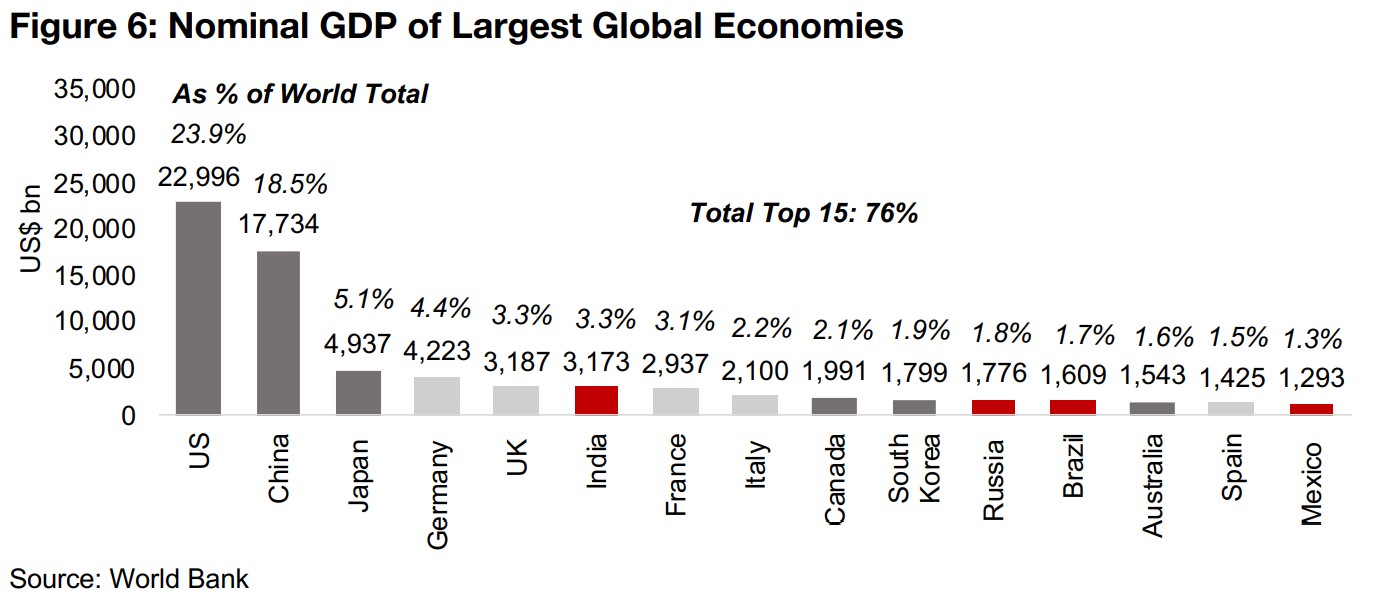

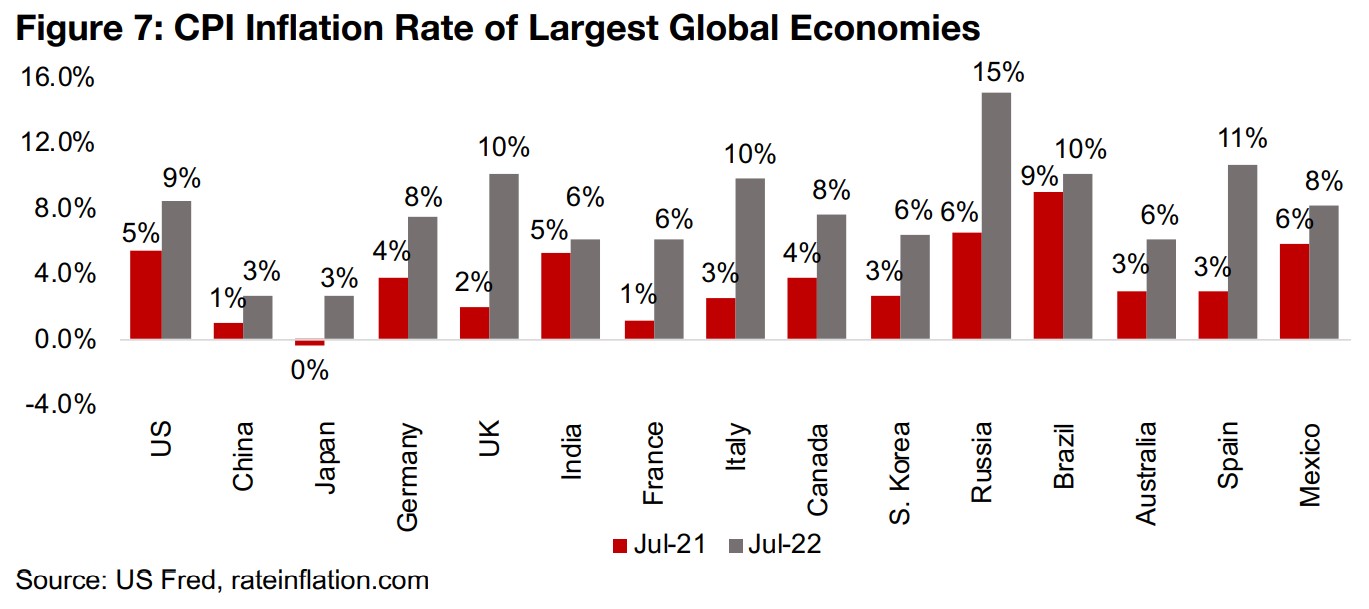

We have focused much this year on US inflation, because the country is such a large global economic driver, accounting for 23.9%, or almost a quarter of world GDP, and with it the first major economy to see a significant spike in inflation over the past year (Figure 6). However, with rising prices becoming an increasingly global problem, this week we look at inflation for the world's fifteen largest economies, which combined account for 76% of the world's GDP, and therefore the majority of world inflation. Comparing July 2022 to July 2021 CPI inflation for these fifteen economies, while all have seen prices increase year on year, twelve have seen inflation more than double, and six seen it more than triple (Figure 7). Only in India, Brazil and Mexico has inflation increased only by a percent or two, and all three of these countries were already facing relatively high inflation rates by July 2021.

All major economies hiking rates in response to inflation

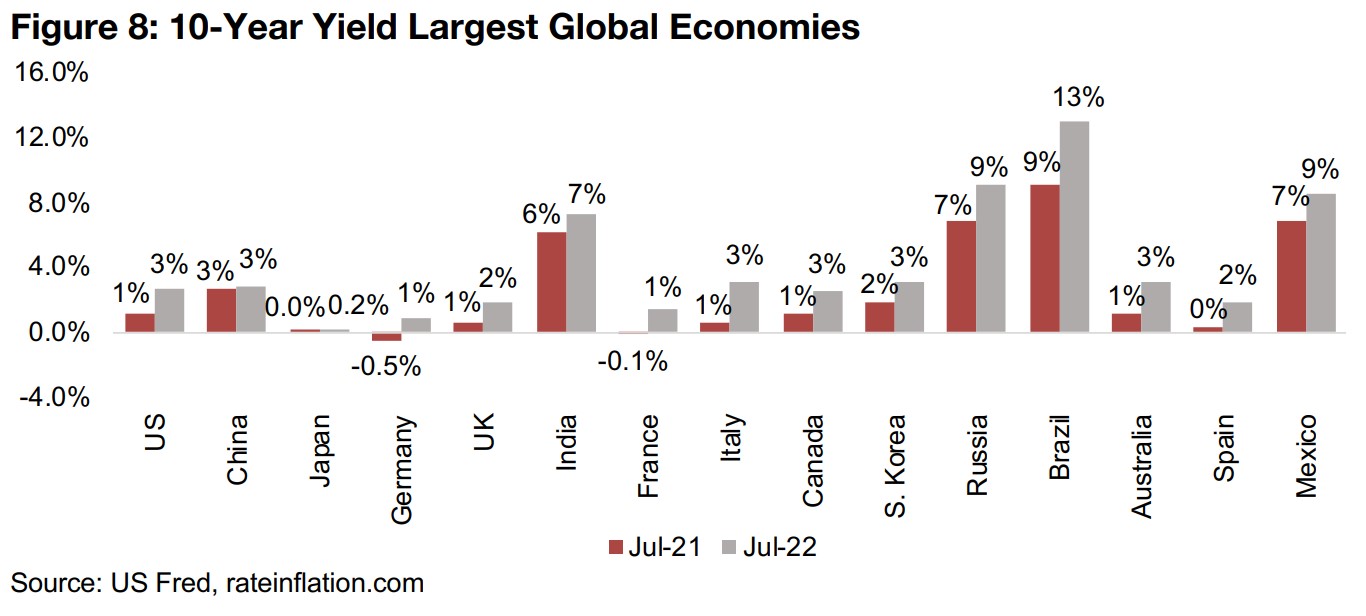

In response to this inflation, the central banks of all these economies have hiked rates over the past year. Using the 10-year bond yield as a proxy for interest rate, for most of the developed countries, last year this rate ranged from slightly negative to around 1.0%, with South Korea an outlier to the upside, at 2.0% (Figure 8). Most of these economies have hiked 10-year rates to 2.0-3.0% as of July 2022, meaning a doubling or tripling of rates. For the developing economies, China's 10-year yield was around 3.0% in July 2021, and it has only increased rates slightly as of 2022, with the rest at around 6.0-7.0% in July 2021, and India, Russia and Mexico all hiking 1.0%-2.0% as of July 2022, with only Brazil standing out for a 4.0% rise.

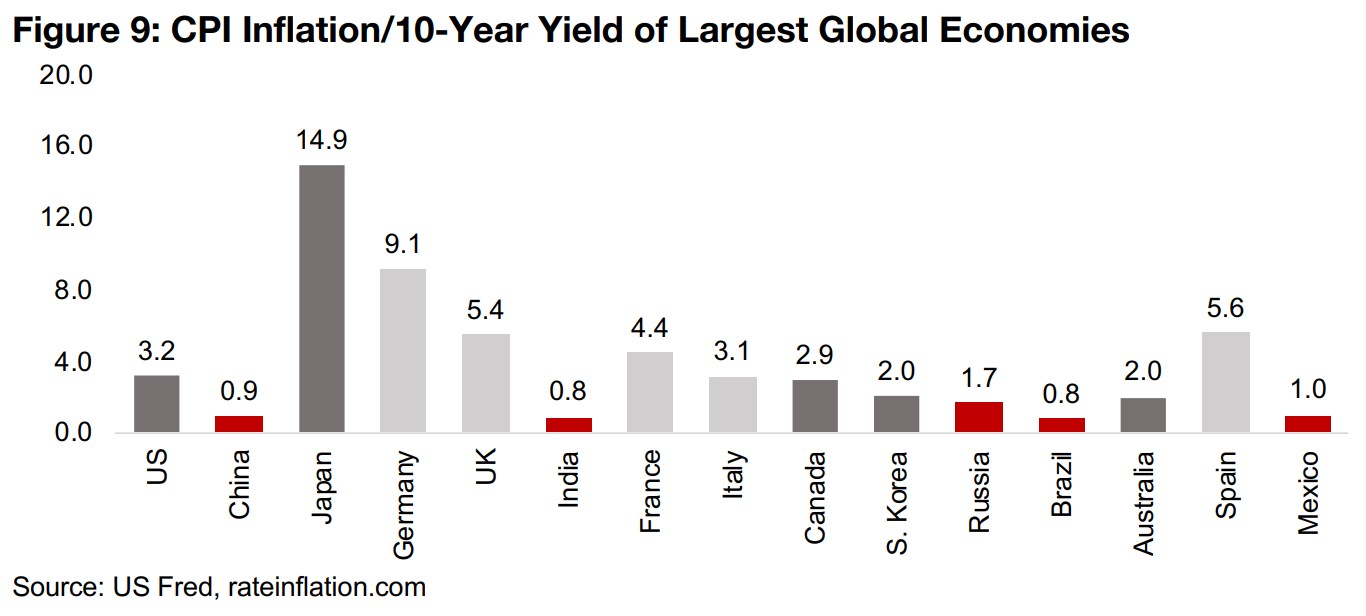

Using inflation over the 10-year bond yield to indicate level of hikes needed

So it is clear from all this that inflation is surging, and there has been a clear rate-hike response from all the major central banks to control this. The question now becomes, 'how far will these central banks have to go to totally curb inflation.' In a recent weekly we investigated this question for the US and came up with a general rule that interest rates have to get close to or even above inflation before it has historically been entirely brought under control. We could therefore use a simple metric where we take inflation and divide it by the interest rate, in this case using the 10-year yield, to determine how far an economy has gone in controlling inflation, and how much farther it has to go. If this figure is at 1.0 or less, then a given economy's interest rate has 'caught up' with inflation, and the rise in prices should theoretically start to fall. As the figure rises above 1.0, it indicates roughly the multiple that rates would have to rise to start substantially bringing down CPI inflation.

Developed economies have a long way to go, developing economies less so

Using this metric we can see that especially the developed economies have a long way to go in terms of completely taming inflation, with all having a ratio of at least 2.0x or higher, meaning that rates would need to more than double from here to curb inflation (Figure 9). Even the US, with its spike in yields versus the rest of the world over the past year, would still need to triple rates from here to significantly reduce inflation. The European countries, which have hiked rates, but not as aggressively at the US, have particularly high ratios, especially Germany, the UK and Spain. Japan's ratio is skewed because its interest rate is just above zero, at 0.20%, but its inflation has reached 2.60%. For the developing economies, the ratio is much lower, with China, India, Brazil and Mexico at 1.0x or lower, suggesting that they may not need dramatic interest rate rises from the current levels to control prices, and even Russia, with the highest ratio of this group, is just at 1.7x, below all of the developing economies.

Can the developed economies really hike enough to curb inflation?

This leads to the question of 'can the developing economies really hike enough to

curb inflation'? What all of this data indicates is that the developed economies are

seriously behind the curve in the inflation fight, even more aggressive actors like the

US, while European economies have some long, hard rate hikes still to come if they

want to pullback price increases. We have to consider the economic fallout of what

a potential tripling or more of rates across the US, Europe and Japan would really

entail, given that the US is already in recession, growth in Europe and Japan is sliding

and global equities have been driven into a bear market. Huge rates hikes would

almost certainly exacerbate these problems, driving a major economic decline and

crashing equity markets further.

We believe therefore that at some point, possibly as early as 2023, that continued

aggressive rate hikes, especially if they start to go global, will simply become

politically untenable. While inflation at such a political tipping point may have come

down somewhat, we don't expect it to have been reduced to the very low levels that

persisted for much of 2012 to 2019 prior to the global health crisis. We may therefore

be moving from a 'no inflation' world prior to the crisis, through the 'surging inflation'

period 2021-2022, to a potentially 'moderate inflation' world from 2023.

Pressure on gold could be short-term if inflation remains high

For gold, all of this is will not help much in the short-run. For the rest of 2022, the US

will likely continue to aggressively hike rates, the US$ could remain strong and US

real yields could get less negative, drawing fund flows away from the gold. We could

also see Europe start to raise rates to fight off their inflation, with levels near the US,

also making their bond yields less negative, pulling even more fund flows away from

gold. Even Japan could raise rates to shore up its plummeting currency, although its

inflation rate remains relatively subdued relative to the rest of the world.

However, eventually, possibly well into 2023, the fallout from rate hikes will become

too much to bear, as we have outlined above, and easy money policy is likely to return.

We believe that this will coincide with still relatively high levels of inflation, which could

be quite supportive of gold. But for now, hawkishness from global central banks looks

set to prevail for at least the rest of this year, which is likely to be bearish for gold,

and doubly for gold stocks, as they are hit by a sliding gold price and equity markets

heavily under pressure from rate hikes.

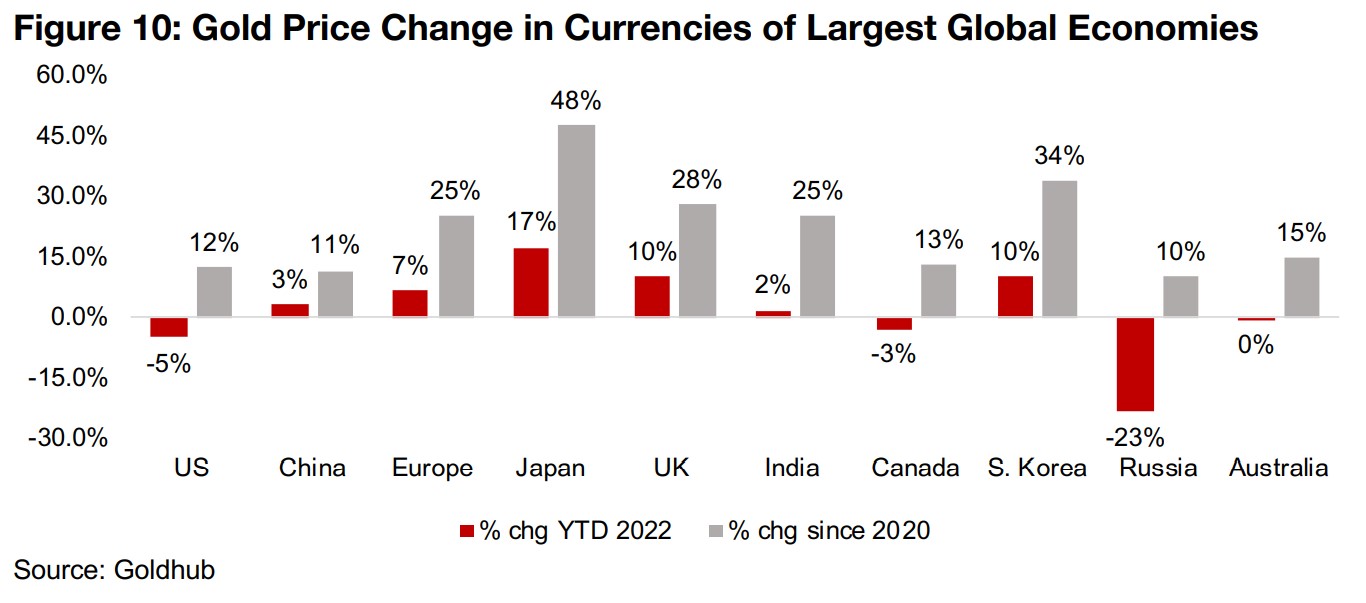

Strong US$ is masking gold's 2022 gains in much of the rest of the world

Another interesting thing to note taking a more international view of inflation and gold is that the price of gold has only declined in 2022 in three of the currencies of the largest global economies, the US$, CAD$ and Russian Ruble (Figure 10). In all other major currencies gold is actually up for 2022, most notably in China and India which are some of the largest global markets for gold jewellery demand. If we extend back to the gains since 2020, gold is up by 10% or more in all the major global currencies. So the pricing of gold in US$, which has surged over the past two years, is actually masking moderate gains for gold in much of the rest of the world.

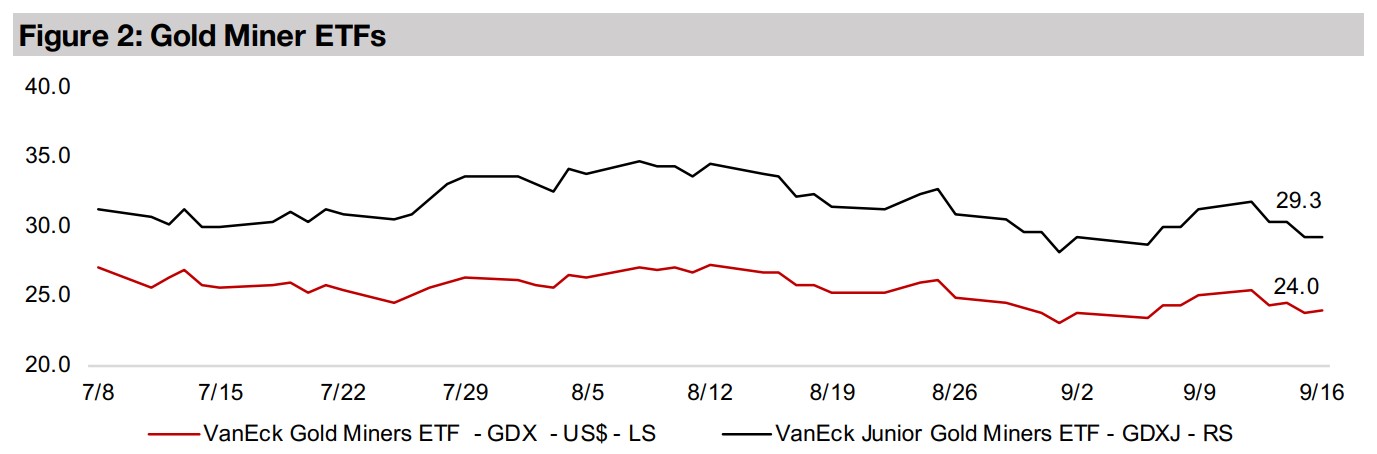

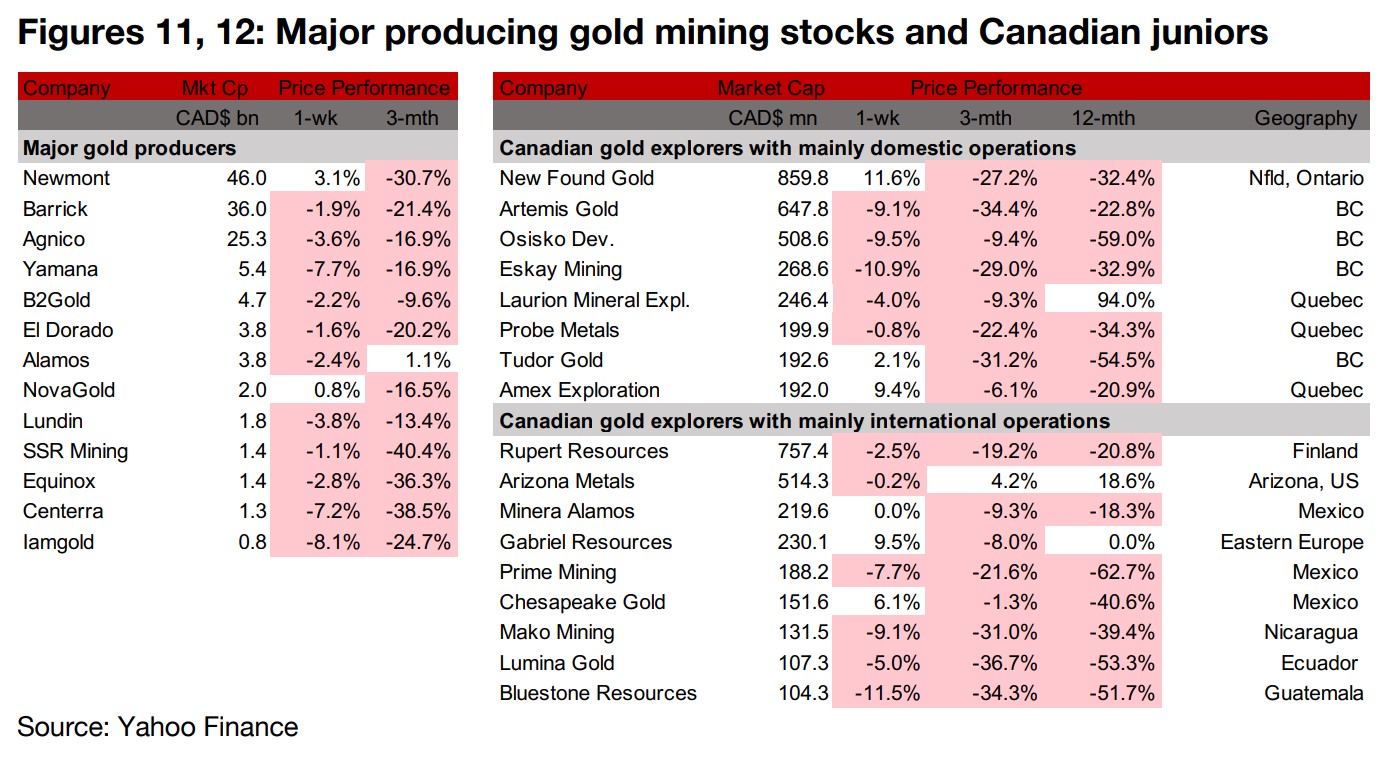

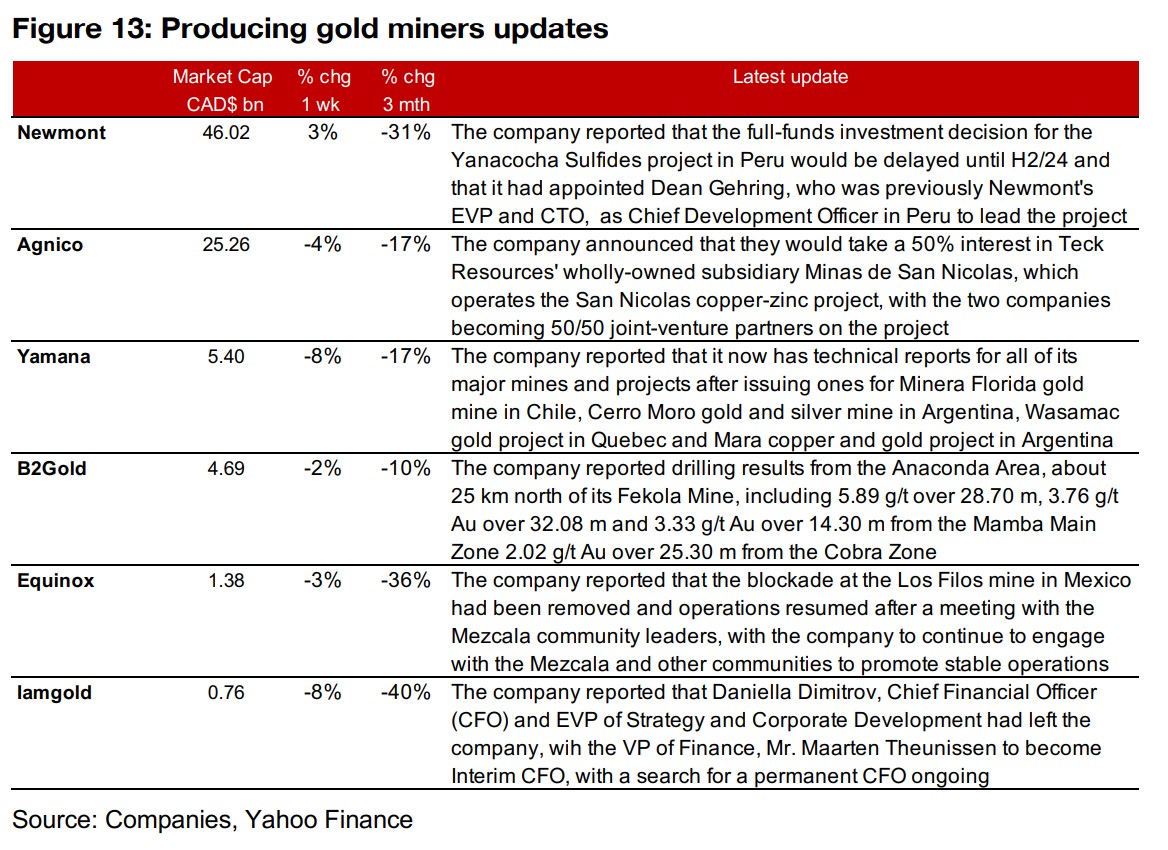

Producing gold miners mostly down on gold and equity drop

The producing gold miners were mainly down on the decline in gold and the equity markets on the expected large rate hike by the Fed this week after August 2022 inflation was higher than market estimates (Figure 11). Newmont reported a delay in the full-funds investment decision for the Yanaocha Sulfides project in Peru and Agnico-Eagle announced that it would take a 50% stake in Teck Resources' Minas de San Nicolas, operator of the San Nicolas copper-zinc project, creating a 50/50 joint venture. Yamana filed technical reports for all of its remaining major mines and projects for which reports had not previously been submitted, B2Gold reported drilling results from the Ananconda Area about 25 km north of its Fekola mine, Equinox announced that the blockade at the Los Filos mine in Mexico had been removed and Iamgold reported that its CFO and EVP of Strategy and Corporate Development Daniella Dimitrov had left the company, to be replaced by Mr. Maarten Theunissen, currently VP of Finance, as interim CFO (Figure 13).

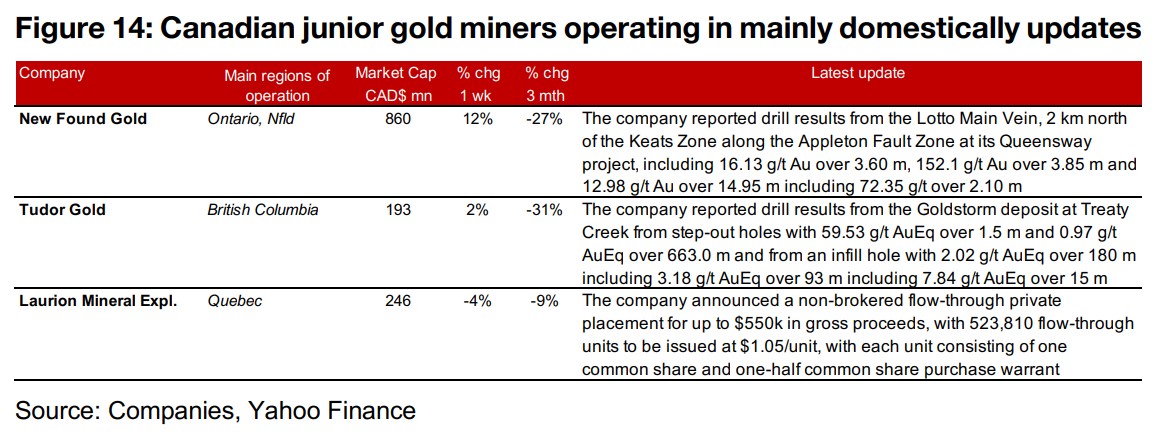

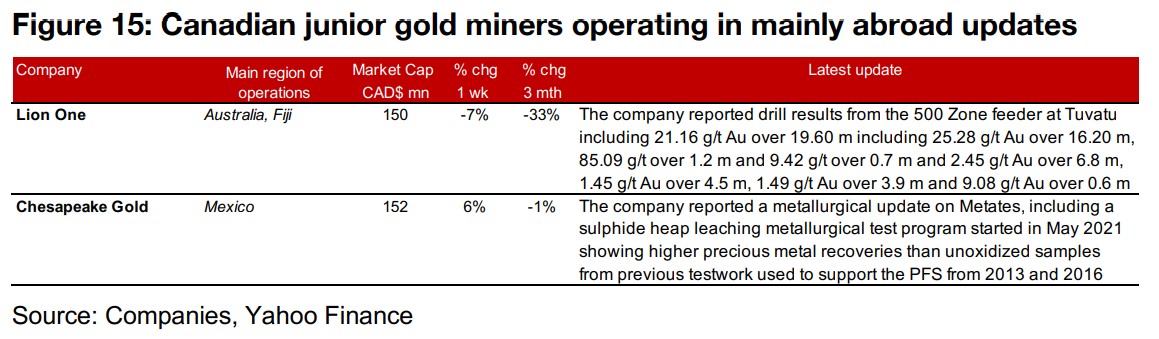

Large TSXV gold juniors mostly down on gold and stock market slide

The larger TSXV gold juniors were mostly down as gold and the stocks market pulled back (Figure 12). For the Canadian juniors operating mainly domestically, New Found Gold reported drill results from the Lotto Main Vein, 2 km north of the Keats Zone of the Appleton Fault Zone at the Queensway project, Tudor Gold reported drill results from the Goldstorm deposit at Treaty Creek and Laurion Mineral Exploration announced a $550k flow-through private placement (Figure 14). For the Canadian juniors operating mainly internationally, Lion One reported results from the 500 Zone feeder at Tuvatu and Chesapeake reported a metallurgical update on Metates showing higher recoveries than testwork to support the PFS from 2013 and 2016 (Figure 15).

Disclaimer: This report is for informational use only and should not be used an alternative to the financial and legal advice of a qualified professional in business planning and investment. We do not represent that forecasts in this report will lead to a specific outcome or result, and are not liable in the event of any business action taken in whole or in part as a result of the contents of this report.