January 15, 2021

Gold Versus its Competitors

Author - Ben McGregor

Gold has biggest dip in ten weeks

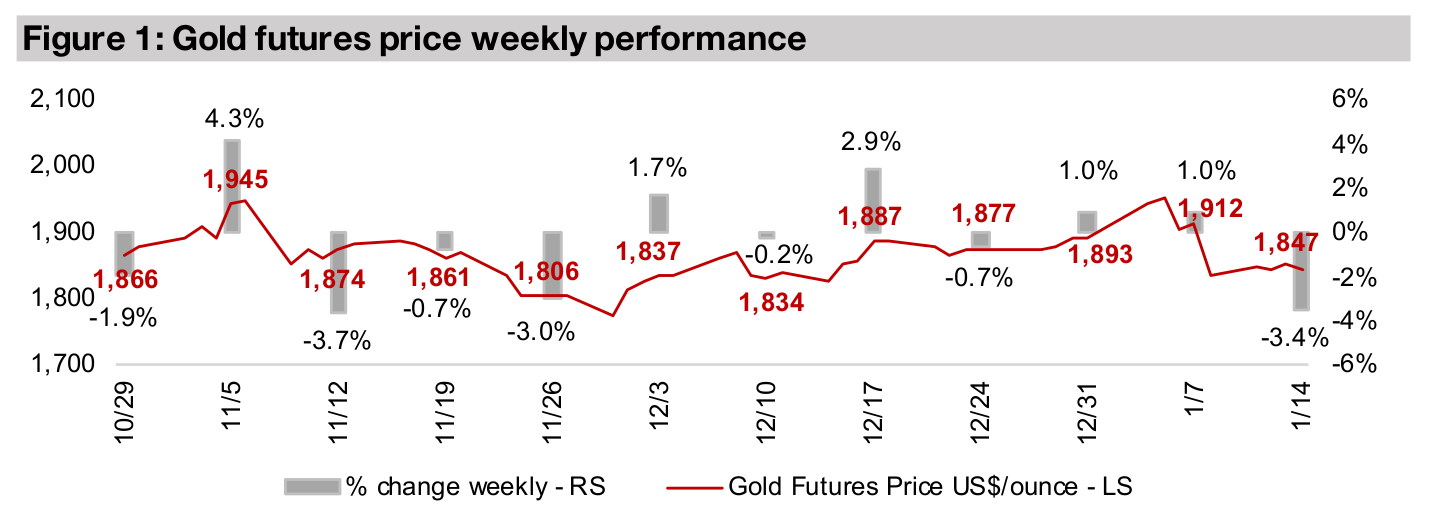

Gold saw its biggest decline in ten weeks, falling -3.4% to US$1,847/oz, with a gain in the US$ and a rise in US bond yields the immediate drivers, while other alternatives to gold have also been seeing recent market interest.

A look at assets competing with gold in the monetary expansion

While we might expect that the massive monetary expansion would have driven gold further, faster, this week we consider alternatives that could be absorbing this liquidity, including consumer spending, equity, bonds, real estate and even bitcoin!

Producers and juniors down on gold dip; BSR.V in Focus

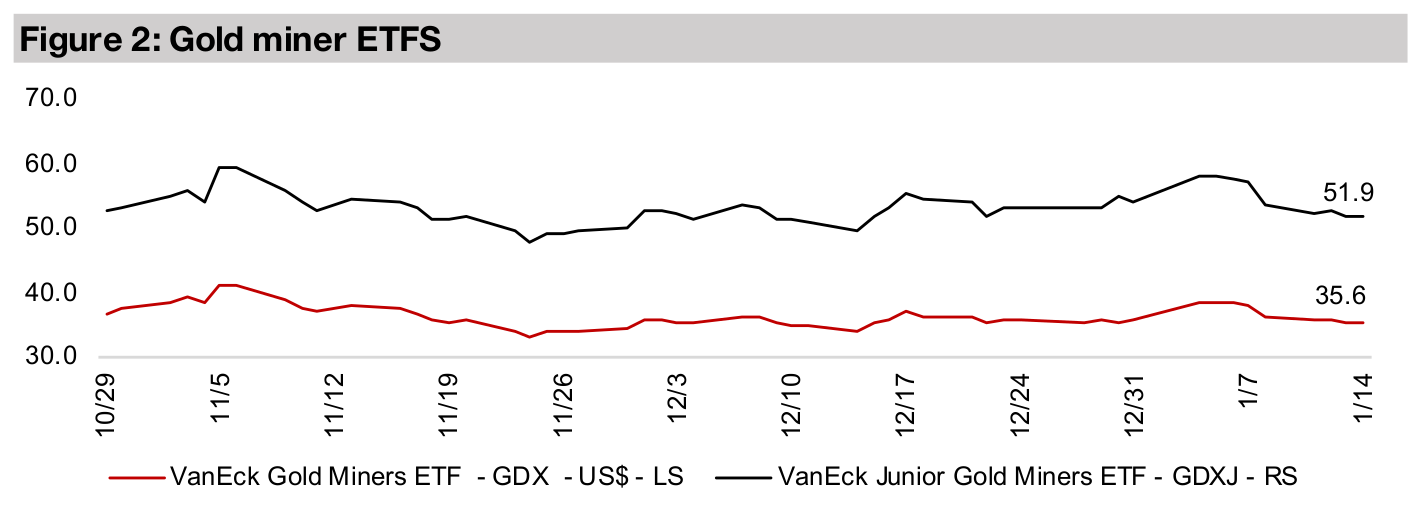

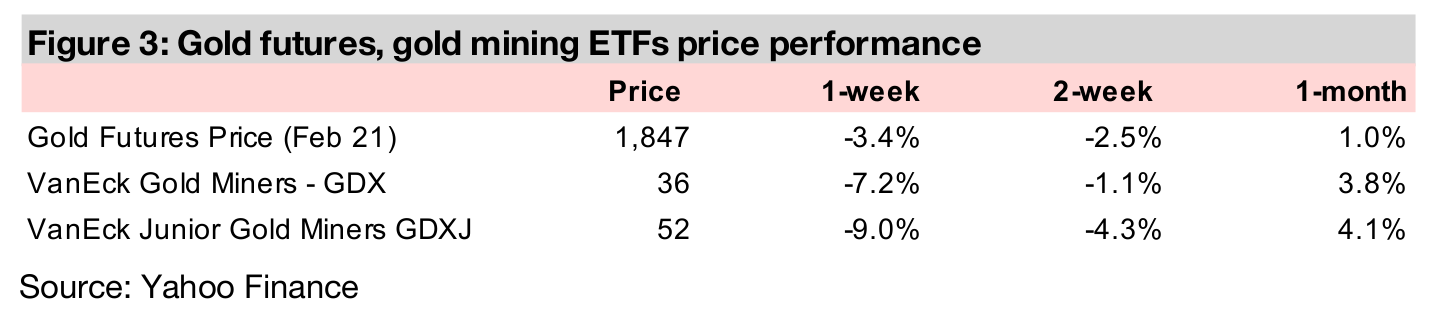

Both the producers and juniors were materially down on gold's decline, with the GDX dipping -7.2%, the GDXJ falling -9.0%, and most Canadian juniors down. Bluestone Resources (BSR.V), at the Feasibility Study stage in Guatemala, is In Focus this week.

A look at gold's competitors for the liquidity explosion

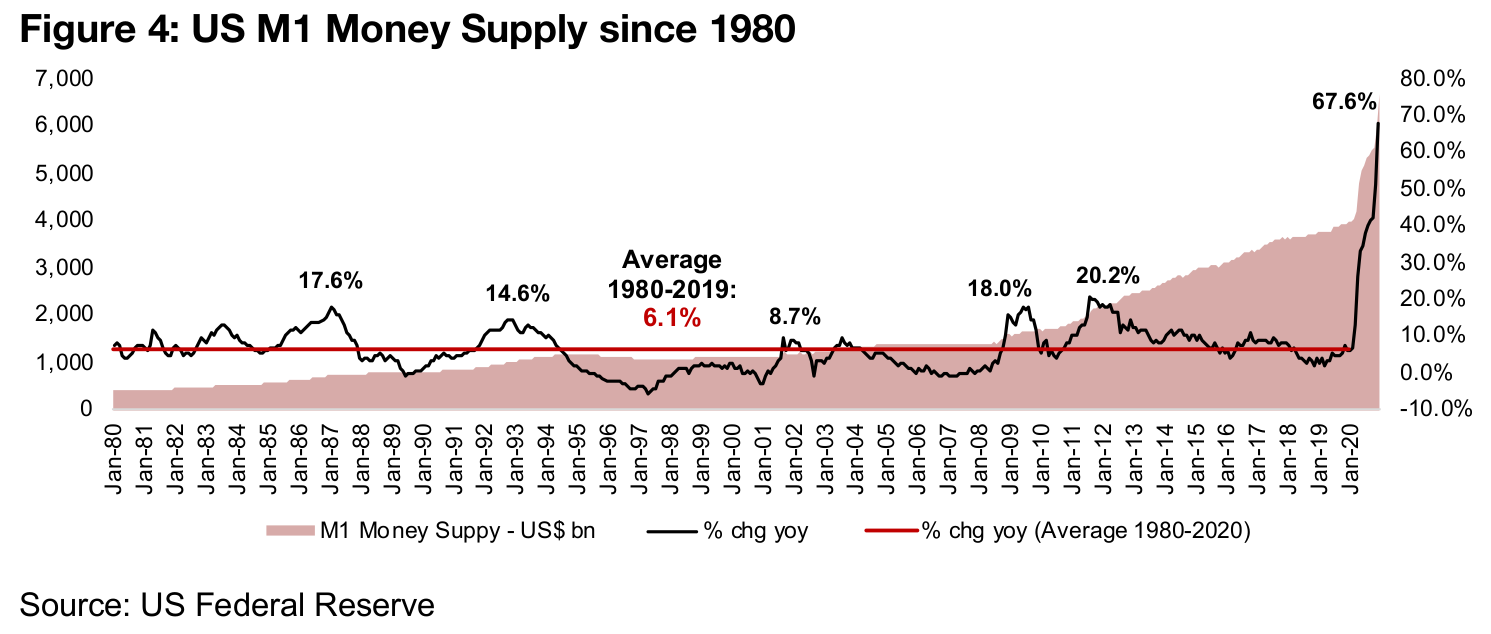

Gold has faced some selling pressure early into the year, even as global risks remain

highly elevated, and a major monetary expansion that went into overdrive in 2020

continues, especially in the US, as shown in Figure 4, with money supply growth at

its highest levels since the country went off the gold standard in the 1970s. We might

expect that this would be better for gold than it has been; the price has certainly been

supported at reasonably high levels, but it has hardly gone parabolic.

The main reason that gold has not done better, even with this liquidity explosion, is

likely because of its many competitors, in our view, that are also of great interest to

investors. This week we look at these competitors compared to gold, including: 1)

general consumption, 2) equity, 3) bonds , 4) real estate, and 5) the newest 'asset

class' on the block, bitcoin. While all of these may continue to steal some of gold's

fire to one degree or another, gold has many unique qualities versus them all which

should mean that it too, continues to benefit highly from the continued liquidity surge.

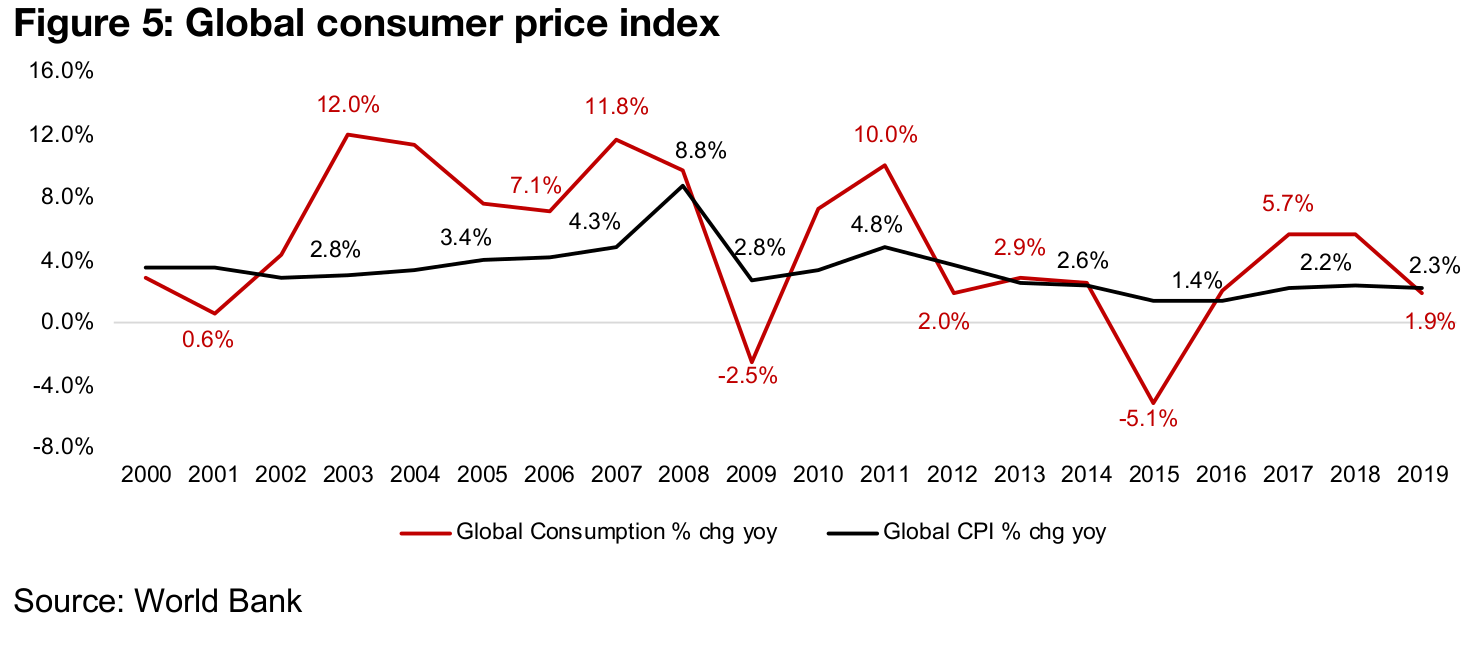

Consumption and consumer price growth remains low

The first place we might expect to see liquidity flow is into consumption, with

businesses and consumers feeling wealthier and potentially more likely to spend.

Interestingly, even with the high levels of monetary expansion over the past ten years,

consumption has not spiked, as shown by the yoy growth in both global final

consumption in US$bn and the global consumer price index in Figure 5.

Overall, global consumption growth has been moderate since 2012, with a

considerable dip in 2015, and only 2017-2018 seeing substantial growth. If there was

a major move into consumption, we would expect prices to jump, and CPI inflation

to be high, but it has been very low over the past five years, suggesting that the

growing liquidity has not been moving heavily into consumer goods. If this trend

continues, we could expect that direct consumption is not likely to draw much of the

current jump in liquidity away from gold.

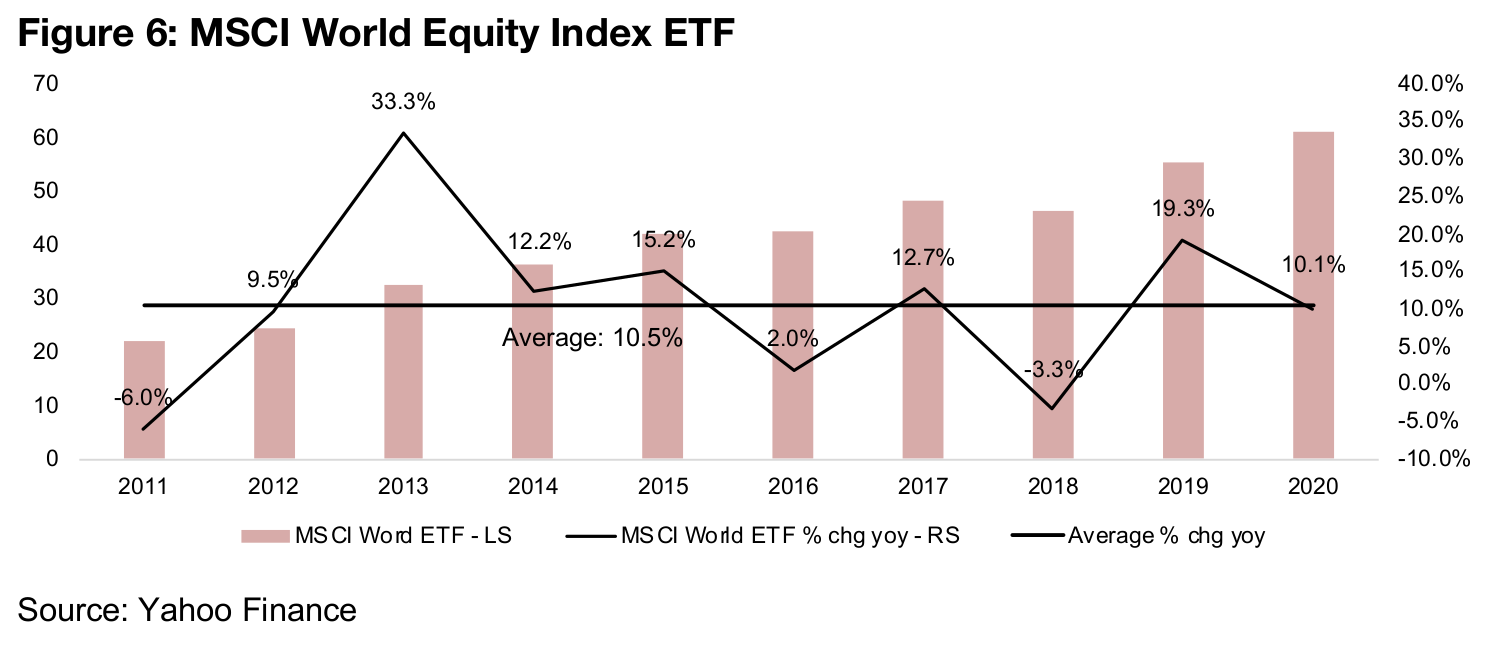

Equity markets have definitely had a boost from monetary growth

Another alternative where rising liquidity can flow is into equity markets. Equity is a

strong alternative to gold as it can generate income through dividends, as well as

very strong capital gains, as stocks can surge many hundreds of percent in a relatively

short time frame. In contrast, gold has no cash flows, and does not have as

aggressive capital gains as equity. However, where equity pales compared to gold is

its very high risk; a stock can go to zero, but gold always retains some basic value.

Much of the high liquidity over the past decade has certainly made its way into equity,

with the MSCI World Equity Index ETF gaining an average 10.5% over the past

decade, with highs of 33.3%, five years over 10%, and just two years of declines

(Figure 6). We can therefore reasonably expect that much of the current liquidity boost

will also be headed for equity markets. However, we do believe that investors have

more of an eye on risk given the shocks of 2020 and currently very high valuations,

which could mean a more cautious move to equity than over the past decade, and

be good for the 'safe-haven' asset gold.

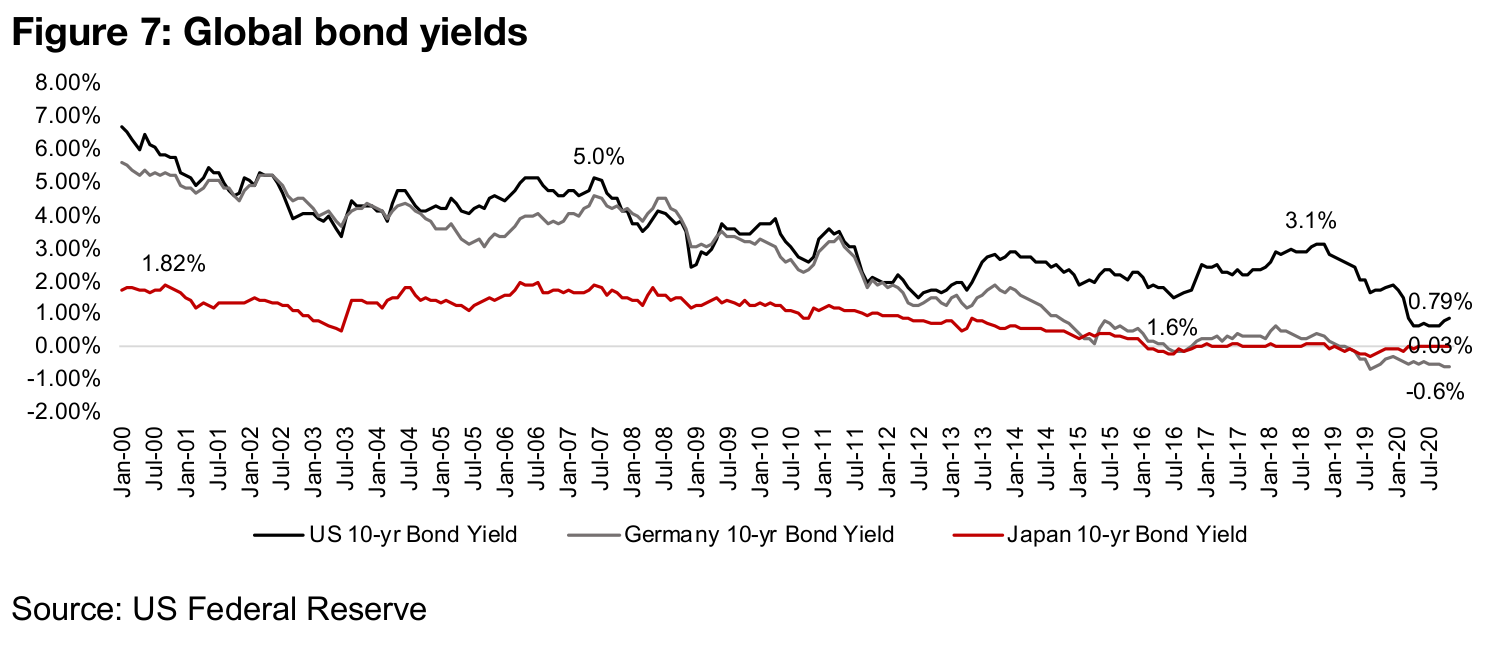

Bonds are also a 'safe' alternative, similar to gold

Putting aside the riskier part of a portfolio, the biggest competitor to gold from the perspective of safety is bonds. Like equity, they provide income in the form of coupon payments, and provide some opportunity for capital gains, although movements in bonds are limited compared to equity. The pricing of bonds is based on yields; as bond yields fall, bond prices rise, and as bond yields rise, bond price fall. Figure 7 shows three of the most significant and liquid bonds (or 'benchmark' bonds) in the largest global bond markets, the 10-year bonds of the US, Germany and Japan. With bonds yields declining for over thirty years (from the 1980s, well before the chart begins), as per the definition above, this means that bond prices have been rising, or more capital is moving into bonds.

Now, it could be suggested that with bonds yields so close to zero, bonds may not

have much room for gains, because yields must fall for bonds to rise, and yields can't

fall much from here before hitting zero. Amazingly, however, yields have broken

through zero, to negative yields; this means that rather than expecting to make a

return, investors are actually paying to hold bonds, a historically strange development.

Nonetheless, if investors are desperate for a safe place to invest, this trend of

negative interest rates, and in turn rising bond prices, could actually continue.

Why would investors do this? Well, one reason is that the bond market is absolutely

massive, and there are not many other markets large enough where this much cash

could be parked; the gold market is tiny by comparison. We could consider negative

rates as good for gold, however, as for some bonds it eliminates the benefit over gold

that they have always had, that they offer a yield over the original price paid. However,

even in the bizarre negative yield environment, given that investors are focusing more

on safety recently, we expect that bonds will continue to be of strong interest, and

be a major competitor of gold, especially within the 'safer' assets category.

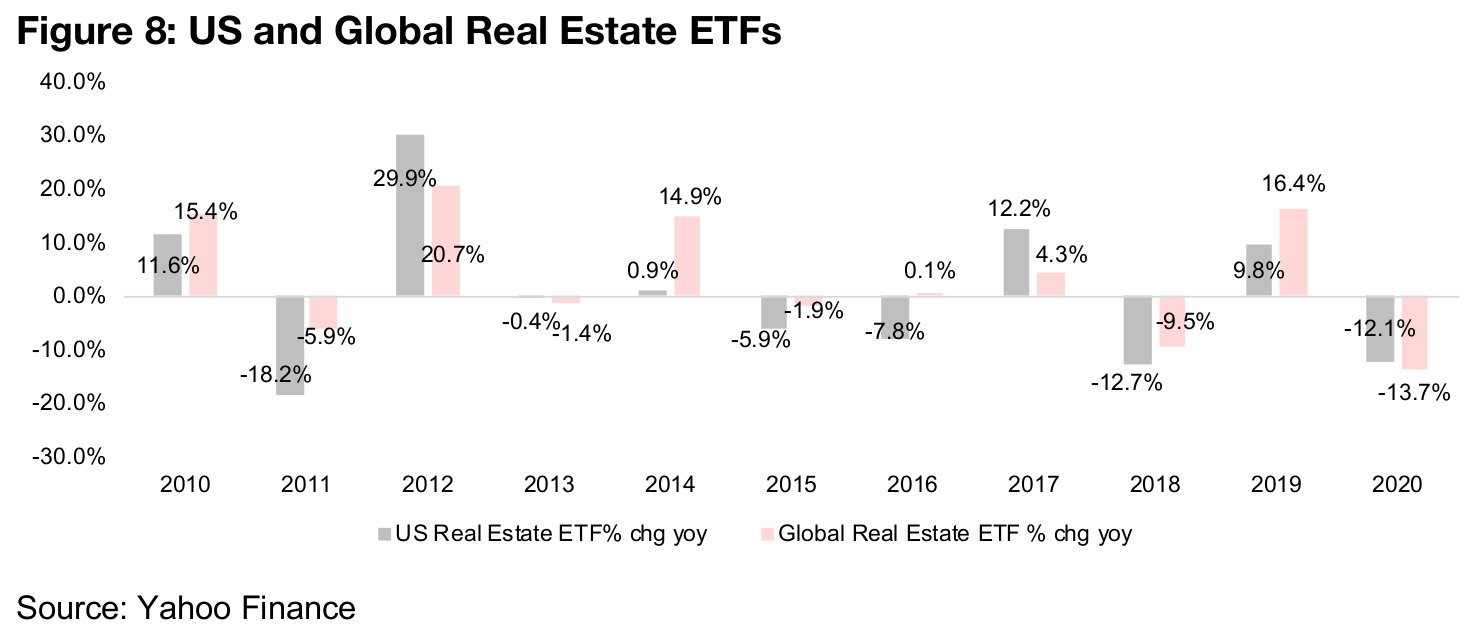

Real estate has seen quite patchy growth over past ten years

Another asset into which liquidity could flow is real estate. Some specific markets, especially major cities in developed markets, have been extremely hot for real estate over the past decade. However, the overall returns from global real estate have been a bit patchy, using the largest US and Global Real Estate ETFs as proxies. Coming out the crisis, both US and global real estate saw strong gains in 2010, a decline in 2011, and peak gains in 2012. However, since 2013, both have been reasonably weak on average, with both 2018 and 2020 seeing considerable declines.

While equity, bonds and gold, are all very liquid, meaning that they can be sold very quickly, real estate is very illiquid, and can take many months to sell, and has a very large unit cost, and cannot be purchased in relatively small amounts like gold or equity. However, similar to gold, real estate has a strong safety element (apart from the extreme 2008-2009 situation), and tends to hold its value over long periods. While real estate in general over the past five years has not seemed to draw in outsized liquidity, if investors shift towards safer assets in 2021, we could see rising interest in real estate, in our view.

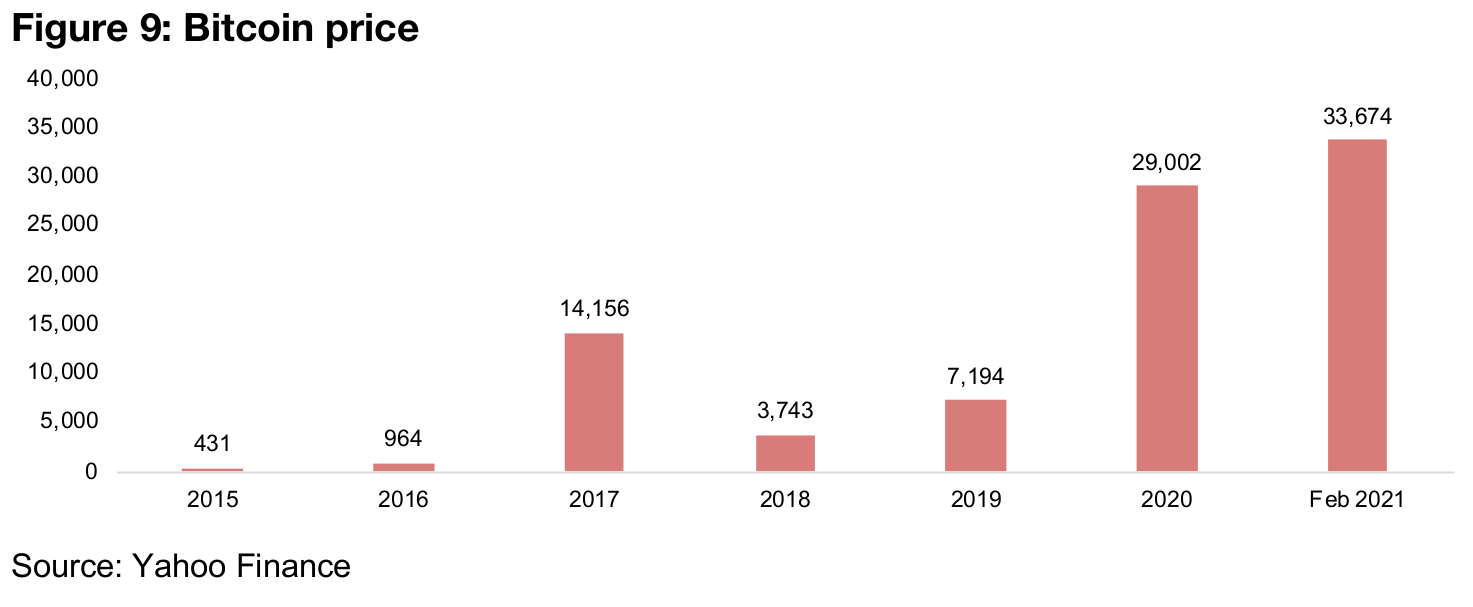

Bitcoin seeing a major rebound

Gold's newest competitor is Bitcoin, the largest cryptocurrency, an entirely digital form of money, which, like gold, is a currency substitute. In contrast to gold, however, it is not tangible or heavily regulated, which does introduce substantial risks, and its price has been particularly volatile, as shown in Figure 9. It also does not have the 3,000-year history as a preferred currency of gold, and has not yet proved it can stand the test of time. In terms of exchange, interestingly, Bitcoin is increasing accepted, and can be used to directly purchase goods certainly more widely than gold. Overall, the recent price action points to Bitcoin gaining a large proportion of the surging liquidity, we believe that it could continue to be a major competitor to gold into 2021.

Gold likely to remain a recipient of the liquidity explosion in 2021

Overall, we believe that gold holds up well, in different ways, than all of these competitors, and therefore is likely to continue to see major inflows as the liquidity surge continues. It provides more safety than equity, it is attractive versus bonds because of currently very low (or even negative!) bond yields, it is much more liquid, and can be purchased in much smaller units, than real estate, and is tangible, and with a much longer proven history as a safe currency and store of value, than Bitcoin. Overall, gold has a combination of strengths not equally provided by any alternative, and thus will remain a unique asset in demand, in our view, as it has for recorded history.

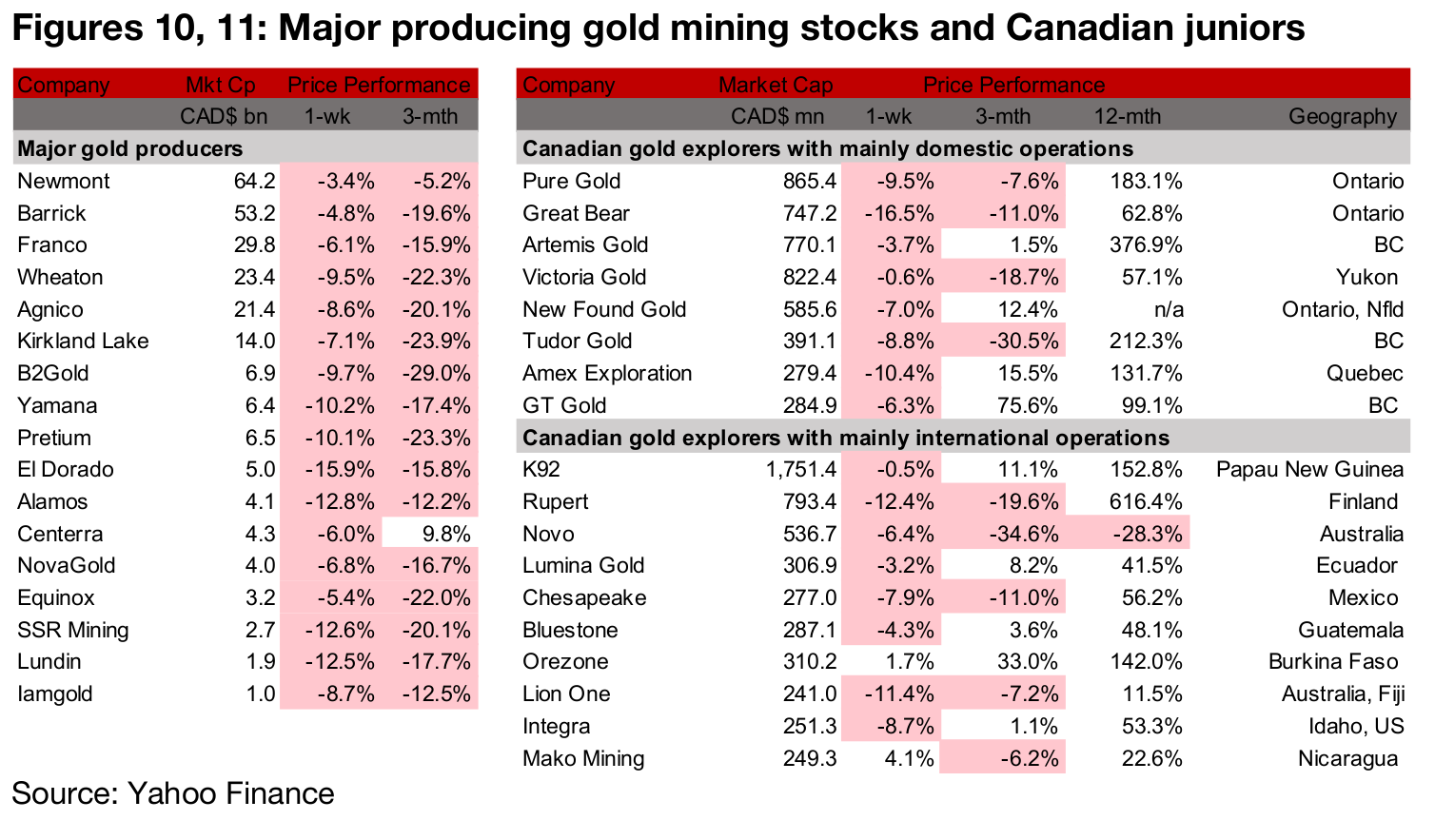

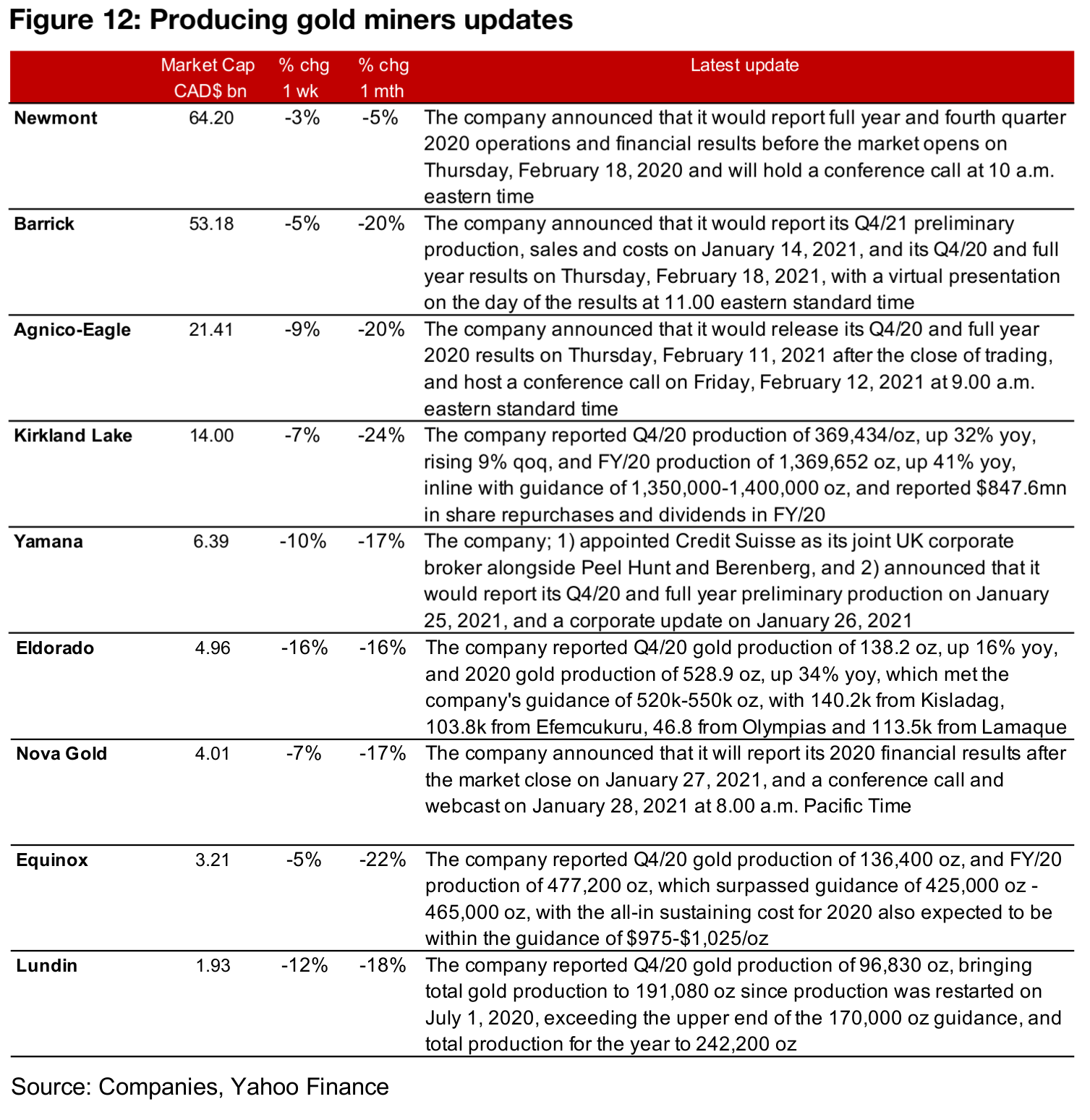

Producers fall on gold decline, Q4/20-related announcements start

The producing miners were all down this week on the fall in gold as well as gains in some competing asset classes, which are outlined in detail above (Figure 10). News flow was mainly related to Q4/20, with Kirkland Lake, Eldorado, Equinox and Lundin all reporting preliminary production figures, and Newmont, Barrick, Agnico-Eagle, Yamana and Nova Gold all announcing the release dates for either their Q4/20 preliminary production or full results announcements (Figure 12).

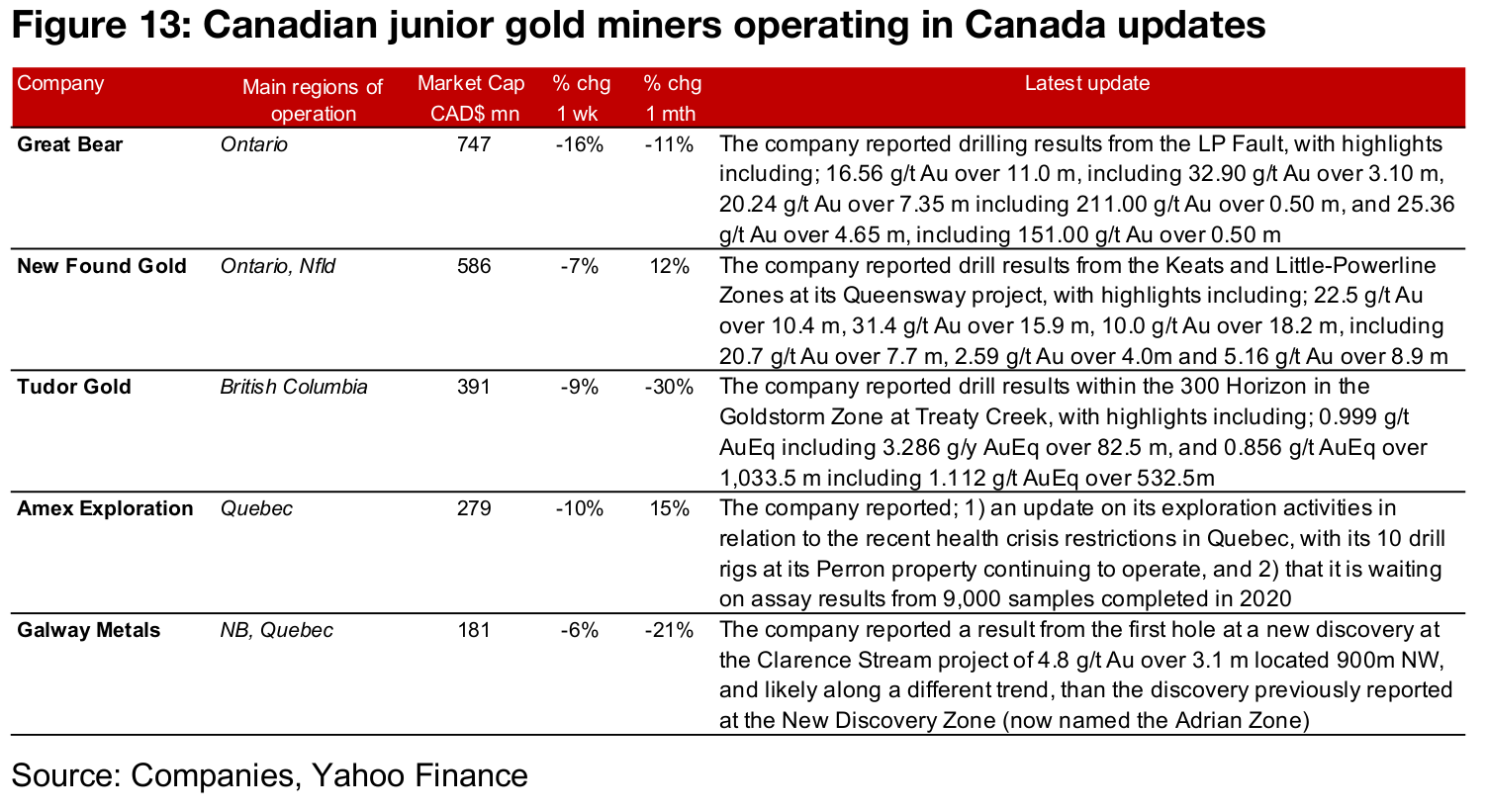

Canadian juniors nearly all down

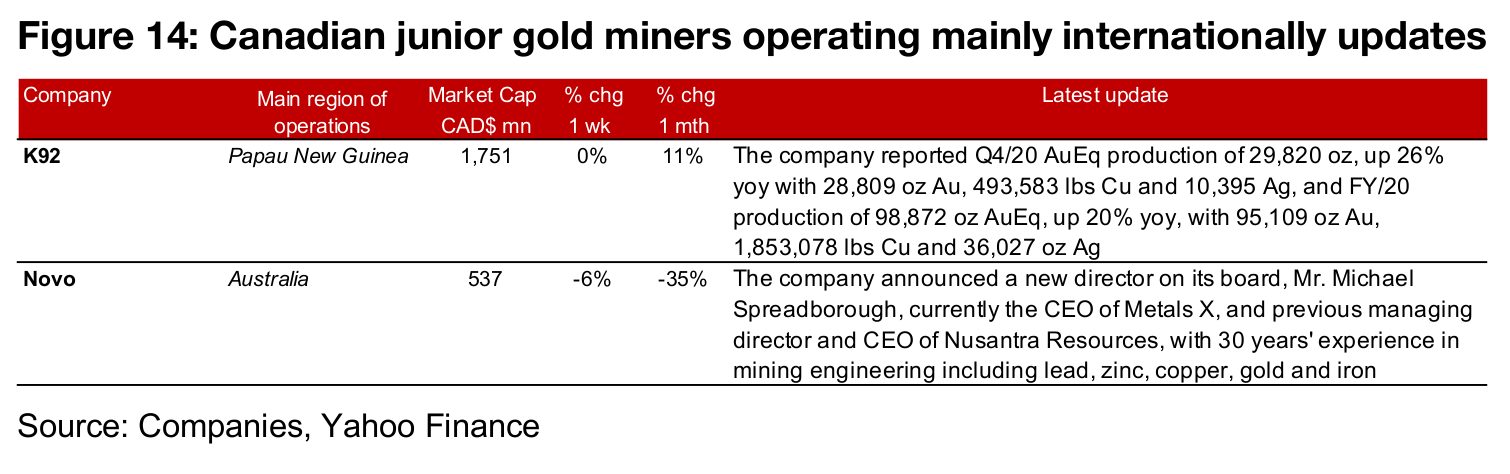

The Canadian juniors nearly all declined this week, with only K92 and Mako holding near flat (Figure 11). News flow from the Canadian juniors operating mainly domestically was mainly focussed on drilling highlights, including from Great Bear, New Found Gold, Tudor Gold and Galway Metals, while Amex reported that its drilling activities at Perron had not been halted by new measures in Quebec related to the global health crisis, and that it was awaiting assay results from samples collected in 2020 (Figure 13). For Canadian juniors operating mainly internationally, K92 reported its Q4/20 production and Novo announced a new director on its board (Figure 14).

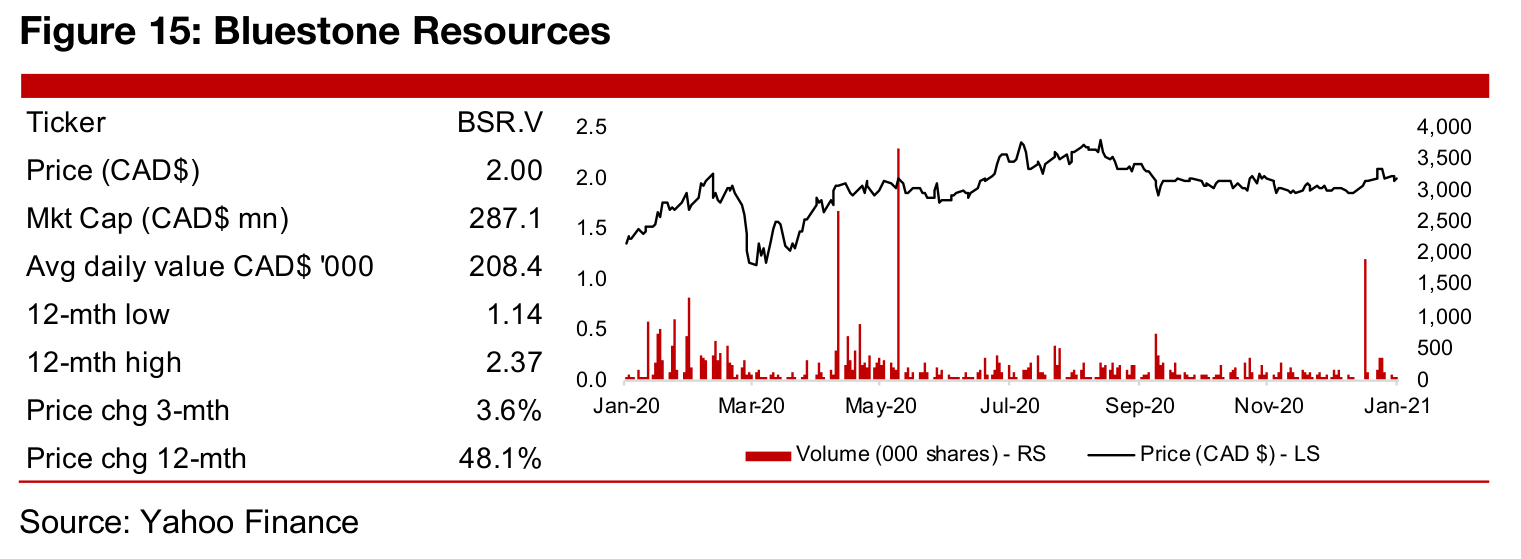

In Focus: Bluestone Resources (BSR.V)

Operates Cerro Blanco, at Feasibility Study stage, in Guatemala

Bluestone Resources operates the Cerro Blanco gold-silver project in Guatemala for which a Feasibility Study was released in January 2019. The company acquired the project in May 2017, then undertook a 20,000 m drill program in 2018, updating the project geology. A Feasibility Study was released in January 2019, and in November 2019, an updated resource estimate, with 1.4 mn oz M&I, up 200 k oz from the original estimate, was reported. In January 2020, Jack Lundin was appointed as CEO, and there were a series of drilling reports through H2/20.

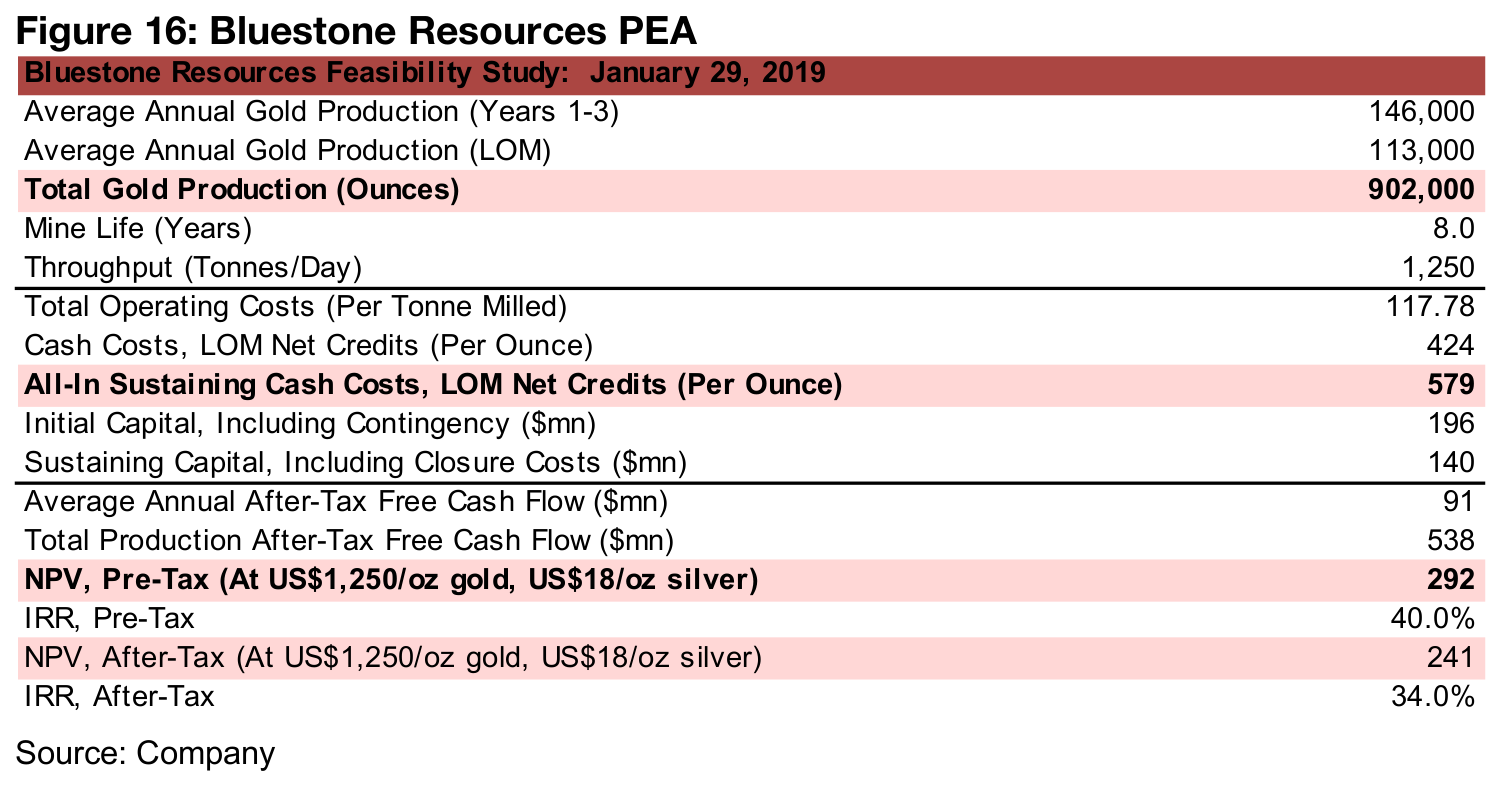

Cerro Blanco NPV up to $454mn

The Cerro Blanco NPV highlights an average LOM annual gold production of 113k/oz, with 146k/oz over years 1-3, with a mine life of 8.0 years, cash costs of $424/oz, all- in sustaining costs of $579/oz, initial capital of $196mn and sustaining capital, including closure costs, of $140mn (Figure 16). The after-tax NPV of the project is $292mn, which is near the current market cap, but this uses a gold price of US$1,250/oz and silver price of US$18/oz. At a gold price of US$1600/oz, the project NPV increases to $454mn, and would have even further upside incorporating the average 2020 gold price US$1,769/oz.

Stock price has held up over H2/20

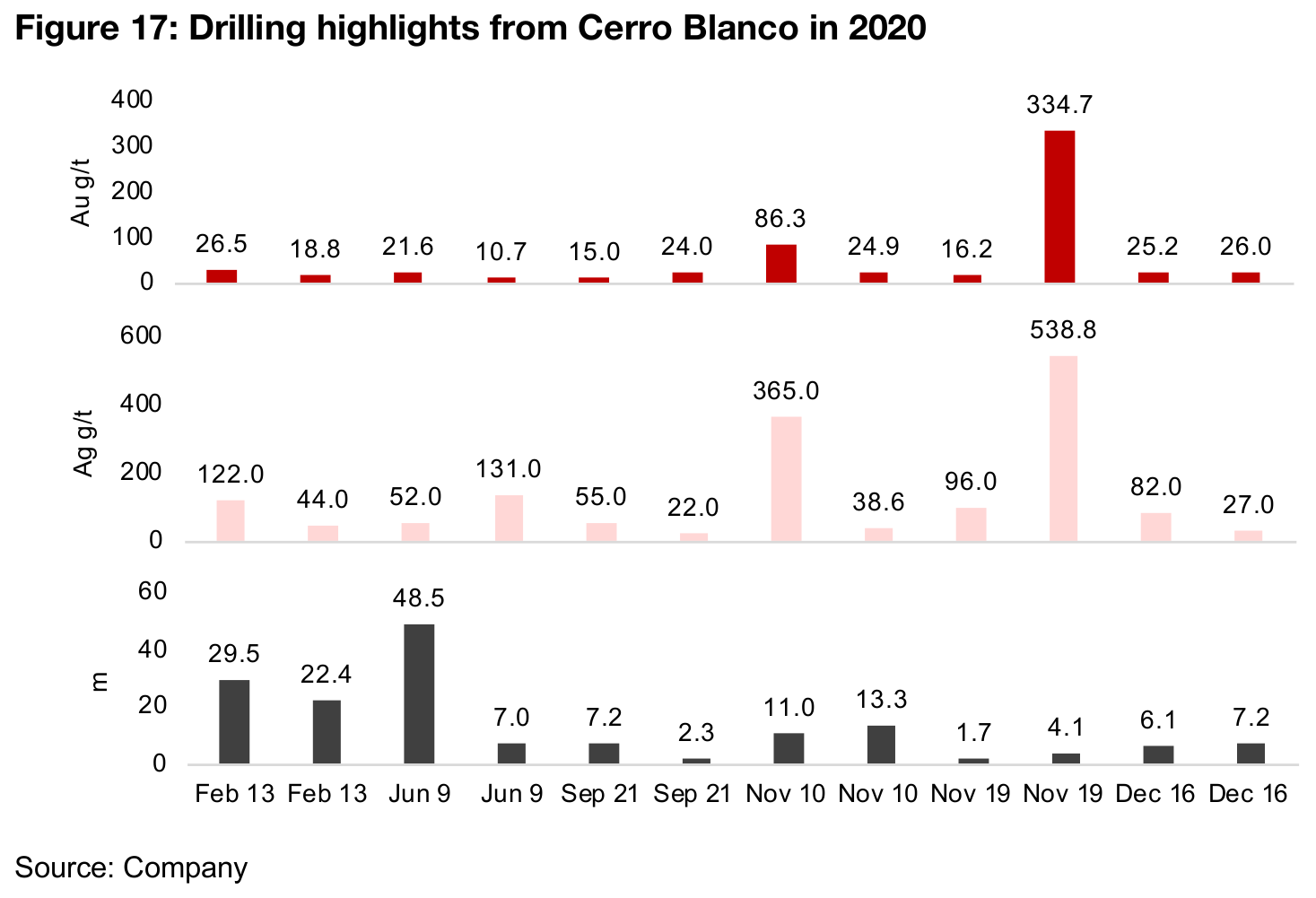

The company's share price held up well in 2020, rebounding strongly from the March crash, and boosted further by C$92mn in financing raised in May 2020, and the stock did not see a major dip even as the gold price retraced into H2/20. The share price was further supported through H2/20 by a series of solid drilling results, with details shown in Figure 17, with the November releases particularly strong. The company is now seeking a financing package, and plans to initiate early works activities and provide an updated resource estimate in Q1/21. The company has support from large shareholders, with the Lundin Family Trust holding 26%, CD Capital 12%, Newmont, 2%, other institutions 35%, management, 5% and retail only 20%.

Disclaimer: This report is for informational use only and should not be used an alternative to the financial and legal advice of a qualified professional in business planning and investment. We do not represent that forecasts in this report will lead to a specific outcome or result, and are not liable in the event of any business action taken in whole or in part as a result of the contents of this report.