October 30, 2023

Gold Breakthrough on Spiking Risk

Author - Ben McGregor

Gold pushes through key level on geopolitical risk surge

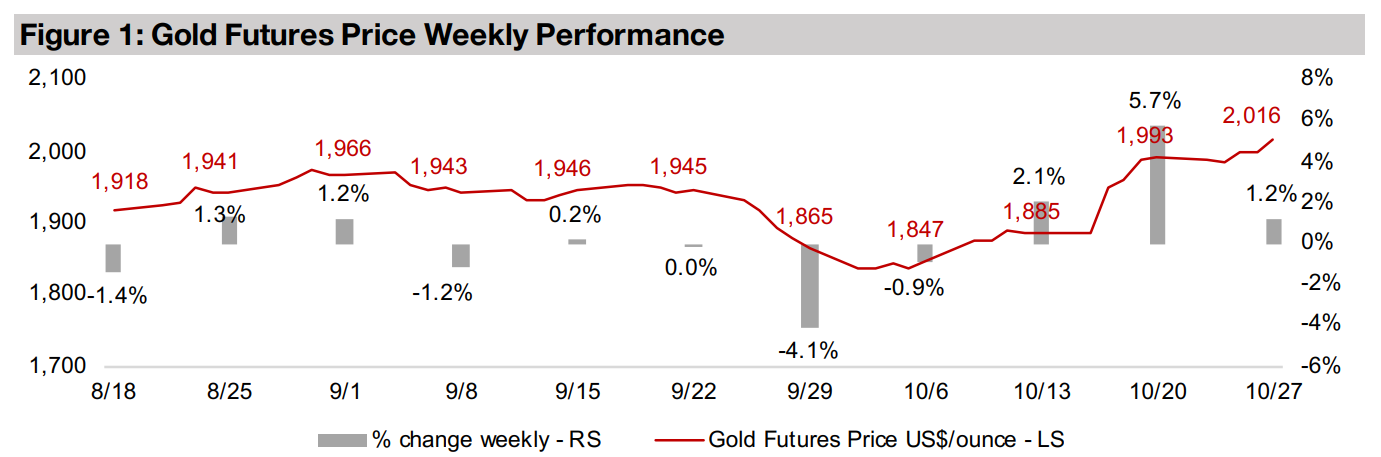

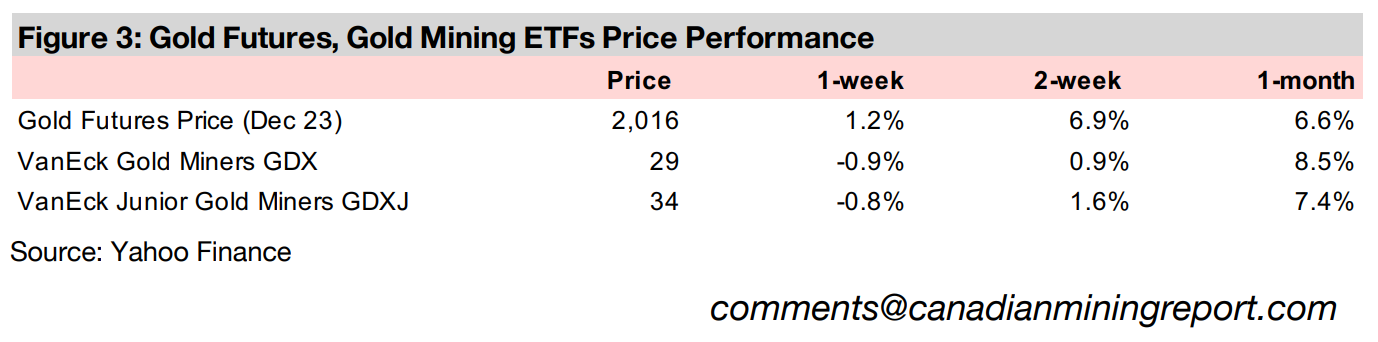

Gold rose 1.2% to US$2,016/oz, breaking through the key US$2,000/oz level for the first time since May 2023 on surging international political tensions, with the Geopolitical Risk Index reaching its highest level since the Russian invasion in 2022.

High demand for physical gold from market and central banks

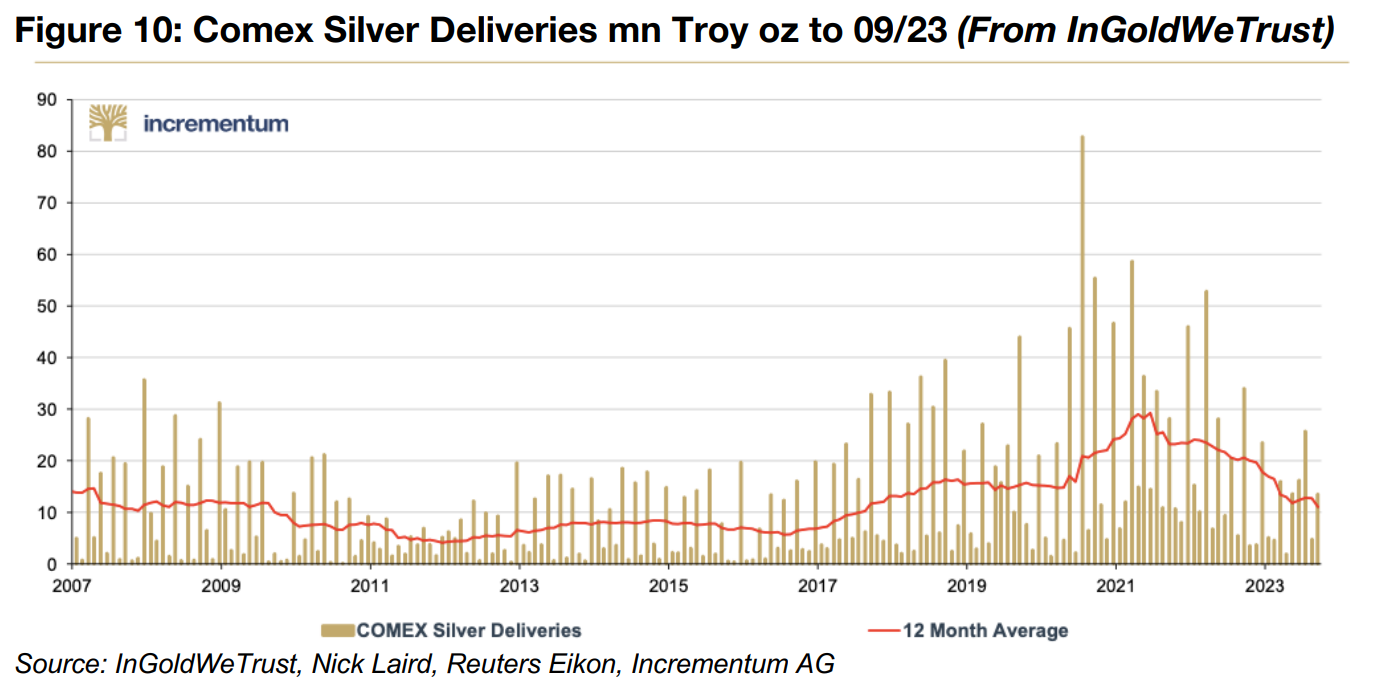

This week we look at two data series showing high demand for physical gold, with Comex deliveries of the metal and silver still elevated, while central banks continue a trend of net gold additions persisting since the 2008 global financial crisis.

Gold Breakthrough on Spiking Risk

The gold futures price rose 1.2% to US$2,016/oz, breaking through the key

US$2,000/oz level for the first time May 2023, and has gained over US$150/oz in a

month. This has mainly been driven by the spike in geopolitical risk over the conflict

centered around the Middle East with concerns that it could escalate into a broader

regional, or even global, conflict. This repeats a pattern we have seen with gold over

the past four years, with major moves above US$2,000/oz tending to have been

driven by major crises, including the global health crisis in early 2020, the Russian

invasion in early 2022 and the banking crisis in early 2023.

However, gold has consistently reverted to its average over the past four years of just

over US$1,800/oz after these crises were offset by other factors. In 2021 this took

the form of a major economic rebound, reducing demand for safe haven assets. Since

2022, it has been underlying fundamentals that tend to pressure gold to the downside,

including rising real bond yields, a surge in the US$ and a decline in the US money

supply. It remains unclear whether the current crisis will be enough to see the gold

price finally hold the US$2,000/oz for an extended period, with the longest so far

above this level in recent years at six days in August 2020 and ten days in May 2023.

Will geopolitical risks offset downward economic drivers of gold?

To the upside for gold, the potential for geopolitical risk to spill over into a wider

regional and even global contagion seems at its highest in a couple of decades. Even

the rise in tensions between major powers following the Russia-Ukraine conflict

seemed subdued and regionally constrained compared to this second conflict in the

Middle East. It already appears to have much wider global ramifications, with rising

tensions between several major powers, exacerbating international relations that

were already on edge. We therefore see the probability weighted towards continued

elevated geopolitical risk, which could support the gold price.

Offsetting this, however, could be the fundamental economic drivers that continue to

move against gold, with inflation still excessive and the US Fed clear that to combat

this it will maintain high rates, and could even hike them further. This could drive up

US real yields and the US$ and contract the money supply further and potentially

drive down gold. These factors could be tempered by a recession that drove up

unemployment, reduced inflation and prompted a return to easier monetary policy by

central banks in response, thus driving up gold on a flight to safety and lower real

yields. However, even with concerns over a potential recession high, there is still little

evidence one is developing, with global unemployment extremely low. This would

suggest any easing of monetary policy is a long way off, and that gold could continue

to pressured by these fundamental factors well into near year.

Overall, we expect that rising geopolitical risk might be enough to gradually drive up

the gold price, but with the fundamental economic factors continuing to attenuate the

rise and preventing a huge breakout to the upside. The biggest risk to this view is that

international relations improve and the global economy remain stable, which could

drive yet another of the reversions towards an US$1,800/oz average that have

repeated since 2019. The longer-term bull case for gold is one where geopolitical risk

continues to spike, a global recession ensues, and there is a resumption of monetary

expansion, which combined could see a dramatic surge in the metal.

While so far we have assumed that an economic downturn would lower inflation and

allow for a return to monetary expansion, there is a third scenario, where a recession

develops, but inflation still persists, referred to as stagflation. In this case it would be

difficult for the Fed to respond with further monetary expansion, as it could drive even

worse inflation. Stagflation has tended to be good for the gold price, with the most

recent bout occurring in the mid-1970s to early 1980s, accompanied by reasonably

low, but rising, geopolitical risk over the period.

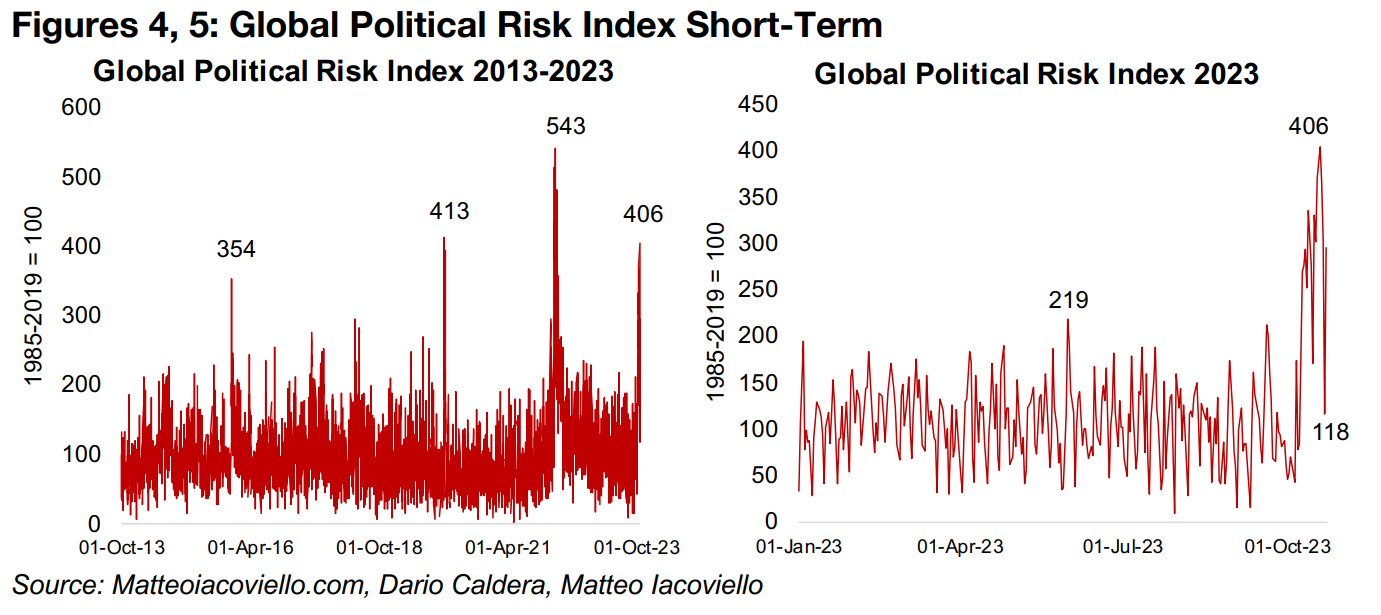

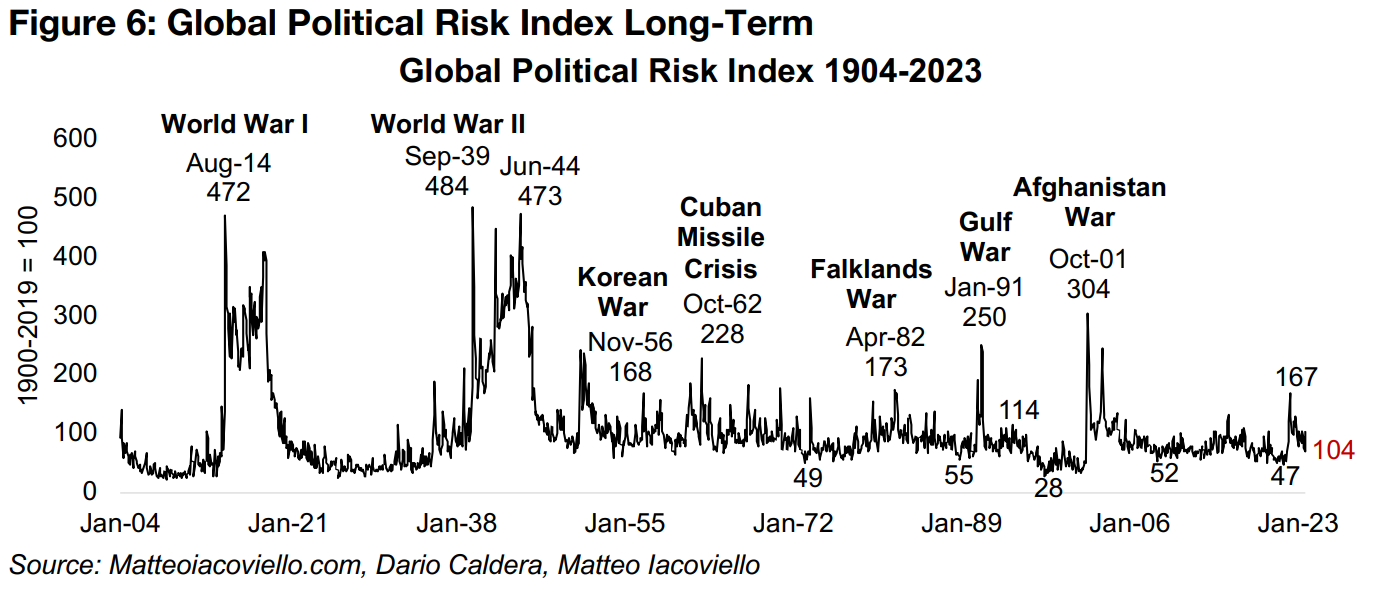

Geopolitical risk index spikes to third highest level of the past decade

While international political risk is nebulous, the Geopolitical Risk Index (GPRI) provides a quantification, based on the number newspaper articles covering geopolitical tensions. The researchers find that a higher GPRI tends to be correlated with a ‘higher probability of economic disasters and larger downside risks to the global economy’. The recent conflict saw the daily version of the index reach its third highest level of the past decade, peaking at 406, below only the 543 reached after the Russian invasion in 2022 and 413 in 2020 during the global health crisis (Figure 4). Looking at just the past year, while the index has declined significantly off this peak to 118, it is still toward the high end of the typical 50 to 150 range (Figure 5).

The Geopolitical Risk Index is also calculated longer-term on a monthly basis back

to the 1900s. However, this is reported only to September 2023, so it does not include

the spike in October 2023 (Figure 6). However, with the daily series showing October

2023 and January 2020 at similar levels, we have assumed this also holds for the

longer-term series and estimate the October 2023 figure at around 104. This puts the

index towards the top of a range mainly holding between 50 to 125 since the 1950s,

with only brief jumps significantly above this level. This suggests that the recent crisis

so far has actually not been that severe in historical terms.

The highest and most extended spikes in the geopolitical index were during the two

World Wars, with a World War I peak of 472 in August 2014 and the index remaining

over 200 for four years from 1914-1918. The World War II peak was 484 in September

1939, and the index remained above 250 for four years from 1942 to 1945. The data

also shows that the period from 2006 to 2019 was particularly uneventful from a

geopolitical conflict standpoint, with only two spikes above 100. If we assume that

the fifteen years of geopolitical tranquility prior to the global health crisis was a

historical anomaly, it would suggest a rising probability of more spikes to come for

geopolitical risk, which will likely be an upside driver for gold.

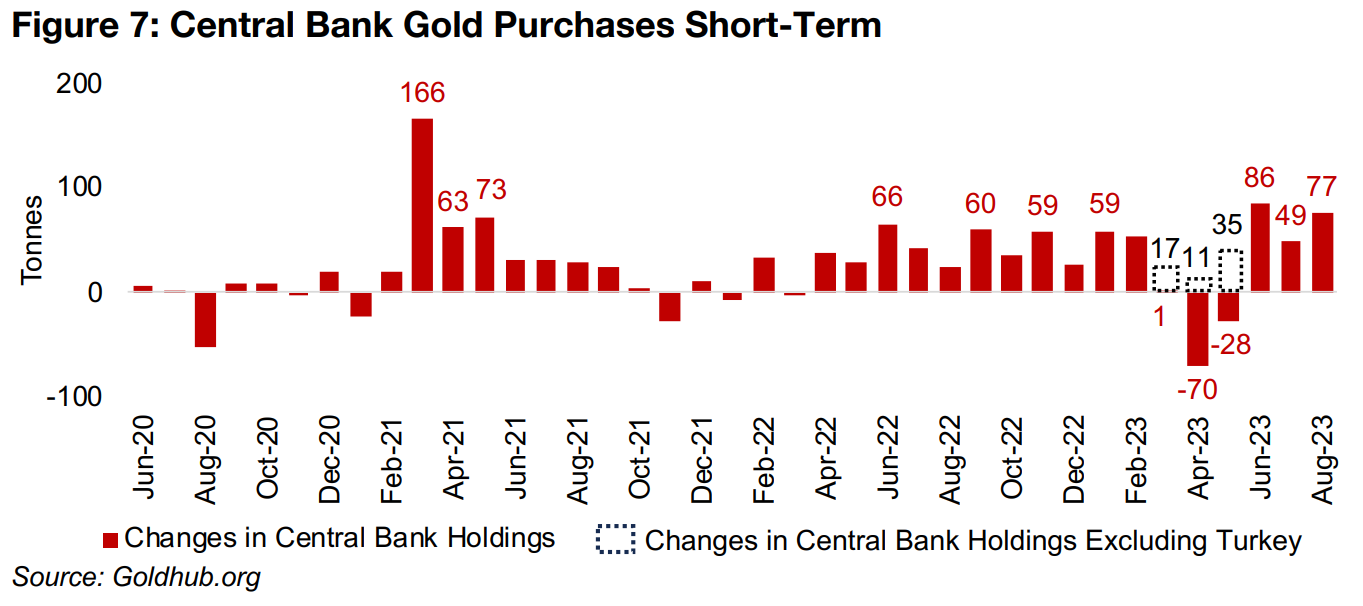

Recent central bank gold net purchases at highest levels since early 2021

The rising risk over the past four years has seen the markets increasingly interested

in holding physical gold relative to ‘paper gold’ either in the form of futures contracts,

ETFs, or other investment vehicles. Central banks continue to build up gold reserves,

adding 86 tonnes of gold to their holdings in June 2023 and 77 tonnes in August 2023,

the highest monthly additions since early 2021 (Figure 7). The trend of significant

additions since April 2022 was only broken from January 2023 to March 2023, mainly

because of sales by the central bank of Turkey.

However, this was not because Turkey had become bearish on gold, but rather

because of large gold sales directly into the domestic market to assist in stabilizing

its financial system. Excluding Turkey, central banks still made net gold purchases

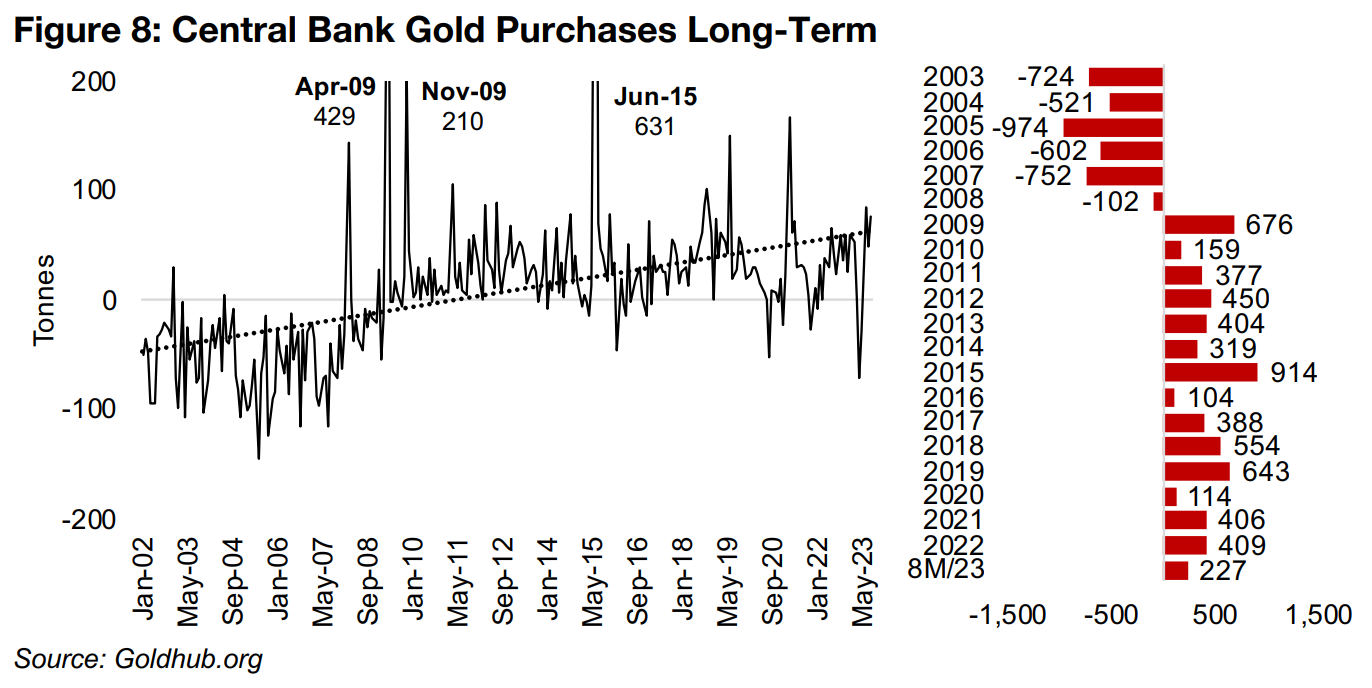

over this period. This trend towards central banks increasing gold holdings goes back

to the 2008 financial crisis, with a shift from average net selling of 714 tonnes per year

from 2003 to 2007 to net buying of 423 tonnes from 2009 to 2022, with purchases

trending up over the past decade (Figure 8). Central banks bought 227 tonnes over

8M/2023, and assuming this trend continues, well over 300 tonnes could be added

by the year-end. Given the spike in geopolitical risk, as well as rising economic risk,

we expect that major gold buying by central banks is likely to continue.

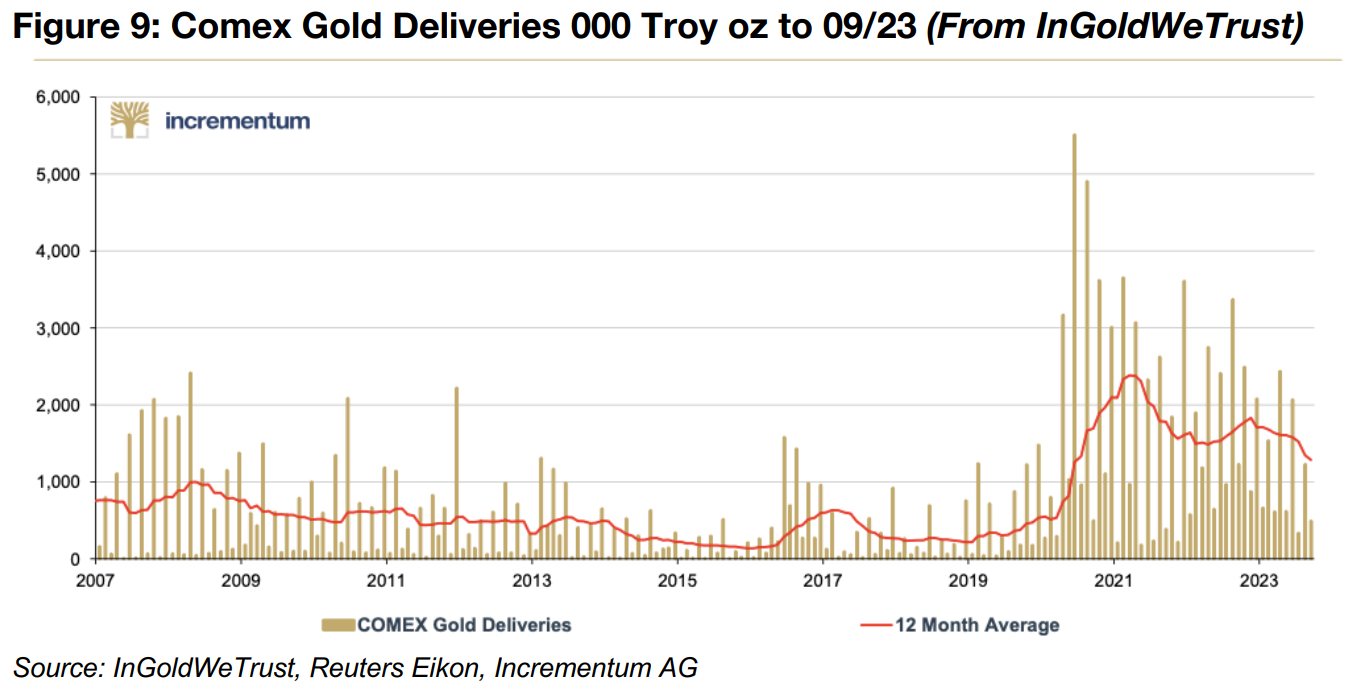

Rising Comex gold and silver deliveries indicate increased risk aversion

Another sign of rising risk aversion in markets is the rise in Comex physical gold and silver deliveries. Comex trades futures contracts, which when nearing expiration are generally rolled over into new contracts, and no physical delivery of the commodity takes place. However, in limited cases the owners of the futures contracts do take physical delivery, and for gold and silver this started to rise as early as 2018 and spiked during the global health crisis. This occurred as more investors became wary of counterparties’ ability to deliver on the paper contracts and they started to prefer holding the physical commodities instead.

InGoldWeTrust show that monthly Comex deliveries peaked for gold at over 5.5mn troy oz, and for silver at 80mn troy oz, in late 2020, with the 12-month averages for both hitting highs in early 2021 (Figures 9, 10). While the 12-month average monthly delivery has declined for both since, it remains still over 1.0mn oz per month for gold, and over 10mn oz for silver. This is will well above the 0.5 mn oz average for gold from 2011 to 2019 and an average around 6.0-7.0 mn oz for silver from 2011-2017. We expect that this demand for physical delivery for both gold and silver could remain elevated in light of continued high geopolitical and economic risks.

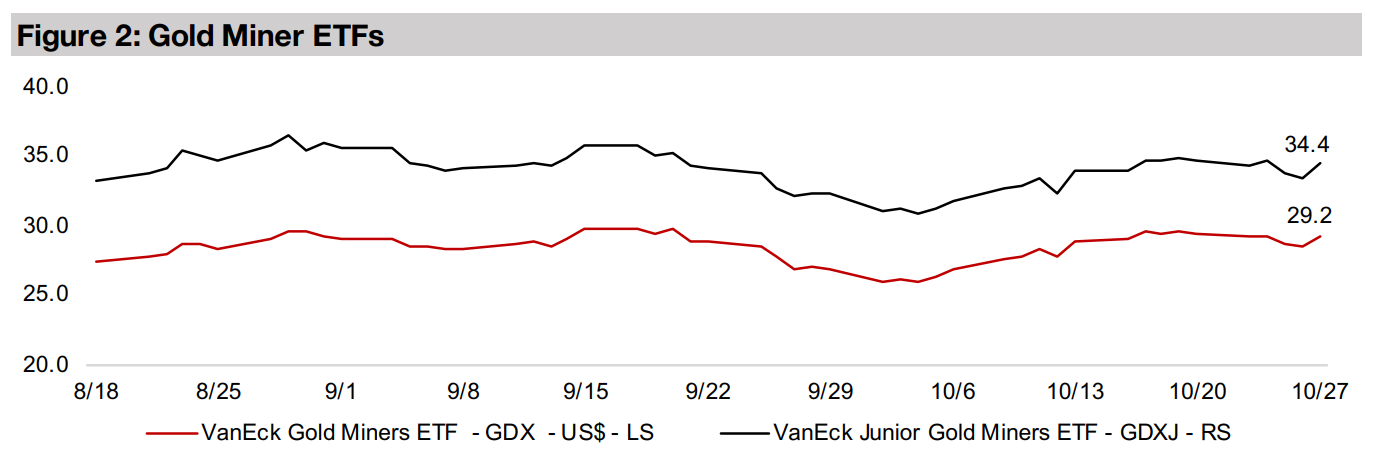

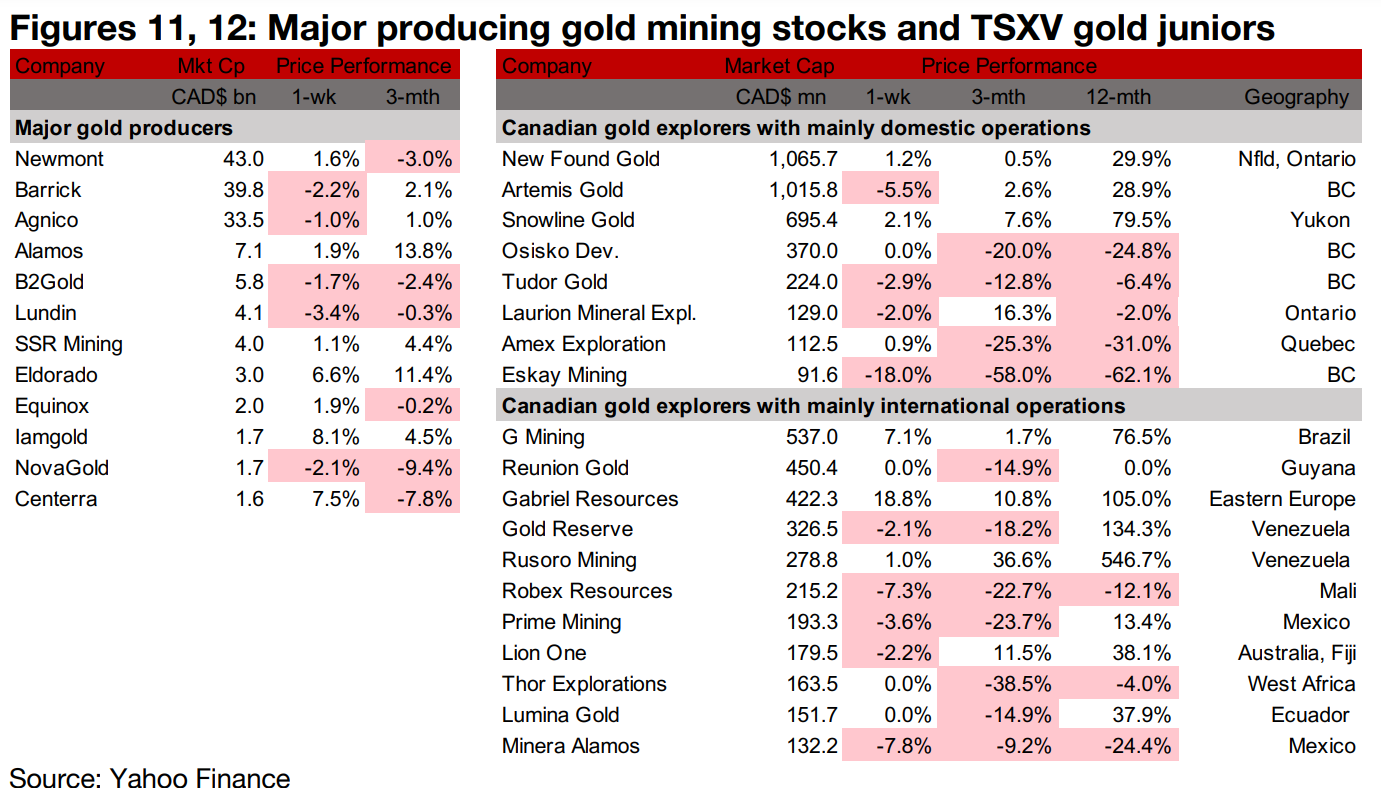

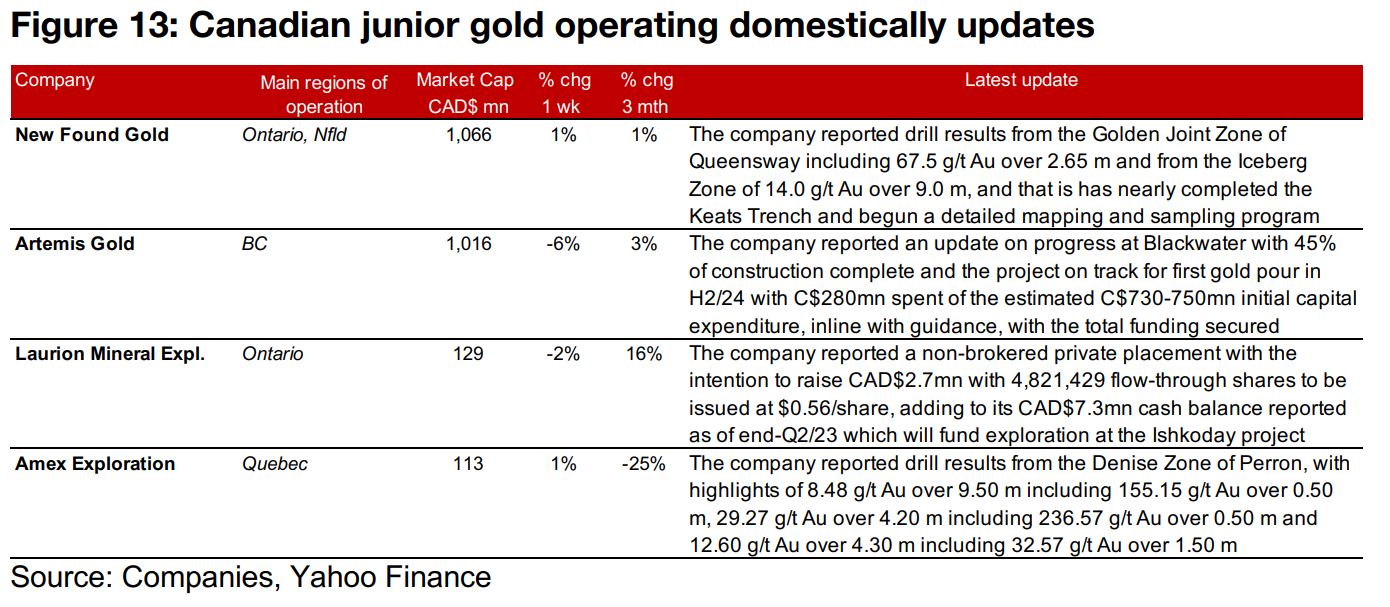

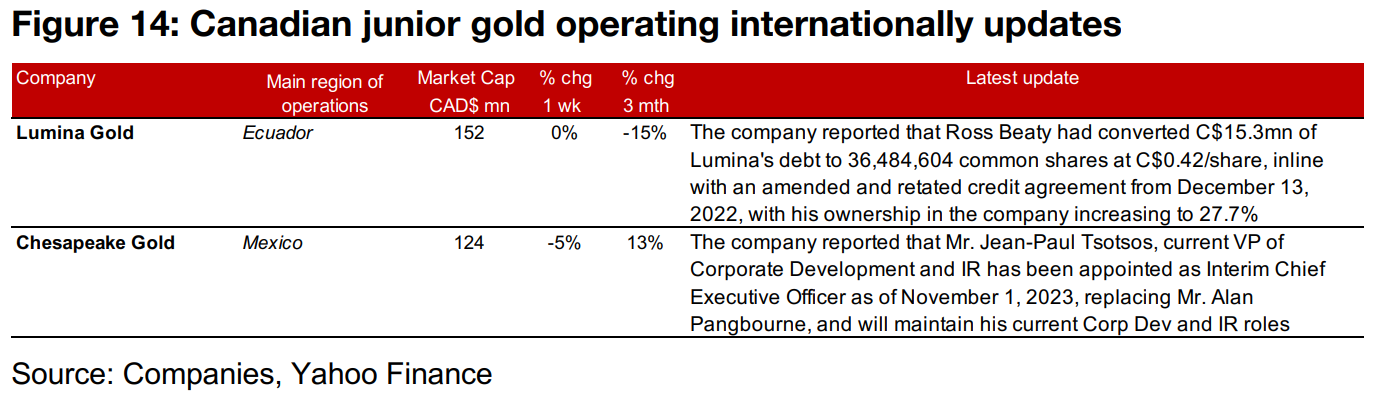

Gold producers rise and TSXV gold mixed

The gold producers and large TSXV gold stocks were mixed as the gold price continued to rise but equities declined (Figures 11, 12). For the TSXV gold companies operating domestically, New Found Gold announced drill results from the Golden Joint and Iceberg Zones of the Queensway project, Artemis reported progress on construction at Blackwater, Laurion Mineral Exploration announced a private placement and Amex Exploration reported drill results from the Denise Zone of the Perron project (Figure 13). For the TSXV gold companies operating internationally, Lumina Gold reported that Ross Beaty converted C$15.3mn of its debt to equity and Chesapeake gold announced the appointment of an interim Chief Executive Officer (Figure 14).

Disclaimer: This report is for informational use only and should not be used an alternative to the financial and legal advice of a qualified professional in business planning and investment. We do not represent that forecasts in this report will lead to a specific outcome or result, and are not liable in the event of any business action taken in whole or in part as a result of the contents of this report.